Your browser is not supported

Sorry but it looks as if your browser is out of date. To get the best experience using our site we recommend that you upgrade or switch browsers.

Find a solution

- Skip to main content

- Skip to navigation

- hot-topics Extras

- Newsletters

- Reading room

Tell us what you think. Take part in our reader survey

Celebrating twenty years

- Back to parent navigation item

- Collections

- Solutions for India's sustainability challenge

- The future of analytical chemistry

- Chemistry of the brain

- Water and the environment

- Chemical bonding

- Antimicrobial resistance

- Energy storage and batteries

- AI and automation

- Sustainability

- Research culture

- Nobel prize

- Food science and cookery

- Plastics and polymers

- Periodic table

- Coronavirus

- More navigation items

Nicholson’s Aereometer

By Andrea Sella 2018-12-17T09:19:00+00:00

- No comments

The forgotten discoverer of electrolysis returns to the spotlight

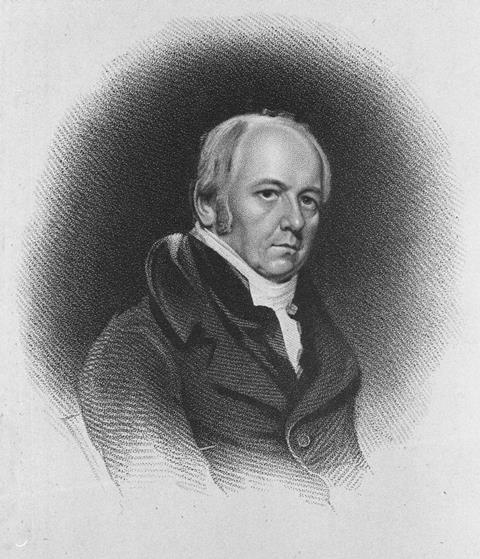

William Nicholson British chemist and journalist (1753–1815). Founder of Nicholson’s Journal and discoverer of electrolysis

‘A fox knows many things, but a hedgehog knows one big thing.’ In 1953, the philosopher Isaiah Berlin drew on this cryptic and mysterious sentence, by the Greek poet Archilochus, to distinguish between the conceptions of history in Russian literature. It’s fun to ask who are chemistry’s hedgehogs and who the foxes? One person to classify might be the hugely influential but largely forgotten figure of William Nicholson, the discoverer of electrolysis.

Source: © Royal Society of Chemistry

William Nicholson British chemist and journalist (1753–1815). Founder of Nicholson’s Journal and discoverer of electrolysis

Born in London to a respectable middle class family, Nicholson made his name with the East India Company, with whom he travelled to China and spent a couple of years in India. When his father died in 1773 he returned to Europe and got a job in Holland as a discreet investigator and agent on behalf of Josiah Wedgwood , who was worried about being cheated. But these short term contracts led nowhere, and Nicholson returned to London where he moved into a house with Thomas Holcroft, a journalist and playwright. Through Holcroft he started getting small writing assignments and minor technical consultancies; he also taught mathematics and translated French novels into English. This succession of small gigs were enough to keep him and his new wife and family housed and fed as he steadily built up his connections in London.

Born in London to a respectable middle class family, Nicholson made his name with the East India Company, with whom he travelled to China and spent a couple of years in India. When his father died in 1773 he returned to Europe and got a job in Holland as a discreet investigator and agent on behalf of Josiah Wedgwood ( Chemistry World , January 2013, p68), who was worried about being cheated. But these short term contracts led nowhere, and Nicholson returned to London where he moved into a house with Thomas Holcroft, a journalist and playwright. Through Holcroft he started getting small writing assignments and minor technical consultancies; he also taught mathematics and translated French novels into English. This succession of small gigs were enough to keep him and his new wife and family housed and fed as he steadily built up his connections in London.

Through Wedgwood, Nicholson became secretary of the General Chamber of Manufacturers of Great Britain. He joined and ran several coffee houses – circles where business, politics or science were discussed. Through the Baptist Chapter Coffee House, of which Wedgwood was a member, Nicholson met many of the leading ‘philosophers’ of the time, including the Portuguese ex-monk and instrument-maker Jean Hyacinthe Magellan, and the phlogistonist chemists Richard Kirwan, Adair Crawford and Joseph Priestley, as well as the Italian-born physicist Tiberio Cavallo.

He also began doing research of his own, driven by his conversations about science. Perhaps inspired by Kirwan, who had devoted much effort to the determination of the densities of salt solutions, Nicholson developed an improved hydrometer.

Hydrometers were nothing new. In the 5th century the brilliant neo-Platonist astronomer and mathematician Hypatia was instructed to build one, a weighted brass tube with notches on its length, corresponding to density, that floated upright. In 1669, Robert Boyle reported the use of glass bulbs to measure the densities of liquids. He refined and developed his idea into a method for assaying coins: the coins could be fixed to the bottom of a hollow metal sphere to which was soldered a rod engraved with a scale. From the buoyancy the density of the coin could be determined.

In the 1770s, the instrument maker Daniel Fahrenheit proposed a new design that would allow the density of any liquid to be determined. The hydrometer consisted of a sealed tube, with a weight at the bottom to hold the device upright in the water. The rod projecting from the top now bore only a single mark. After weighing the device dry, it was floated with weights added to the dish until it floated with the mark level with the water. Next, with the device immersed in the test liquid, the process was repeated. The ratio of the two laden weights gave the density.

In 1784, Nicholson combined the Boyle and Fahrenheit approaches. His device was equipped with a dish at the top and a basket at the bottom. It floated at the mark in water with a weight of 1000 grains loaded on the dish. The loading would change in a different liquid, analogously to Fahrenheit’s device. But working with distilled water, the basket could be loaded with a known mass of unknown solid. Adjusting the weights at the top gave the weight of displaced water, from which the density of the solid was easily calculated, with excellent precision.

Alongside his scientific contributions Nicholson wrote at a phenomenal rate from textbooks to encyclopaedias, and translating French chemistry texts by Fourcroy and Chaptal. He also began Nicholson’s Journal , a direct rival to the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions . Upset by the competition, the Royal Society’s secretary Joseph Banks turned down Nicholson’s candidacy for Fellowship on the grounds that the society was no place for ‘sailor boys’.

In 1800, Banks received a manuscript from Alessandro Volta describing his ‘battery’, a stack of alternating copper and silver coins that provided a continuous source of electrical sparks. Banks discussed this with a friend, the surgeon Anthony Carlisle, who turned to Nicholson for help in replicating the experiments. Needing to connect the stack of coins to an electrometer they added a little water to improve the contact. To their surprise they saw bubbles in the liquid. Intrigued they put the wires from their battery into a tube of river water and saw streams of bubbles from each wire – hydrogen and oxygen, the components of water suspected by Lavoisier. They published immediately in Nicholson’s Journal . The paper lit the fuse that led Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution, who had himself learned chemistry on Nicholson’s texts, to the isolation of the alkali metals.

In 1800, Banks received a manuscript from Alessandro Volta ( Chemistry World , June 2011, p58 ) describing his ‘battery’, a stack of alternating copper and silver coins that provided a continuous source of electrical sparks. Banks discussed this with a friend, the surgeon Anthony Carlisle, who turned to Nicholson for help in replicating the experiments. Needing to connect the stack of coins to an electrometer they added a little water to improve the contact. To their surprise they saw bubbles in the liquid. Intrigued they put the wires from their battery into a tube of river water and saw streams of bubbles from each wire – hydrogen and oxygen, the components of water suspected by Lavoisier. They published immediately in Nicholson’s Journal . The paper lit the fuse that led Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution, who had himself learned chemistry on Nicholson’s texts, to the isolation of the alkali metals.

In spite of his fame, Nicholson struggled to make ends meet. Deeply in debt, his journal was taken over by the more successful Philosophical Magazine . He died at home in London in 1815, his name almost forgotten except, perhaps, by geologists who used his hydrometer. A jack of many trades, a master of many, perhaps he was a superposition of both hedgehog and fox.

W Nicholson, Mem. Litt. Phil Soc Arts , 1784, 370

- Classic kit

- Culture and people

Related articles

Chemistry wordoku #073

2024-12-13T14:30:00Z

By Hamish Kidd

Quick chemistry crossword #066

2024-12-13T14:15:00Z

By Paul Board

Cryptic chemistry crossword #066

2024-12-13T14:00:00Z

Cryptic chemistry crossword #065

2024-12-06T14:00:00Z

Chemistry wordoku #072

Quick chemistry crossword #065

No comments yet, only registered users can comment on this article., more opinion.

Extracting treasure from trash

2024-12-10T13:00:00Z

By Derek Lowe

Taking the long view from 2024

2024-12-09T15:00:00Z

By Philip Robinson

Letters: December 2024

2024-12-06T09:28:00Z

By Chemistry World

The moral theories behind climate deadlock

2024-12-05T09:38:00Z

By Vanessa Seifert

The carbon capture conundrum

2024-12-03T16:21:00Z

By Neil Withers

Learning to listen

2024-12-02T15:54:00Z

By Phillip Broadwith

- Contributors

- Terms of use

- Accessibility

- Permissions

- This website collects cookies to deliver a better user experience. See how this site uses cookies .

- This website collects cookies to deliver a better user experience. Do not sell my personal data .

- Este site coleta cookies para oferecer uma melhor experiência ao usuário. Veja como este site usa cookies .

Site powered by Webvision Cloud

- Grinnell College

- Physics at Grinnell

Nicholson's Hydrometer

Description

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

William Nicholson (born 1753, London, England—died May 21, 1815, Bloomsbury, London) was an English chemist, discoverer of the electrolysis of water, which has become a basic process in both chemical research and industry.. Nicholson was at various times a hydraulic engineer, inventor, translator, and scientific publicist. He invented a hydrometer (an instrument for measuring the density of ...

Nicholson Hydrometer Oscillation. In subject area: Engineering. ... Nicholson and Shain revolutionized the voltammetric experiment with their elegant development and demonstration of linear-sweep and cyclic voltammetry. In their approach, the current-potential curve is presented as ... Nicholson (1965) has published, ...

Experiment 1 Apparatus Nicholson's hydrometer, weights, cylindrical container for immersing the hydrometer, liquid whose S.G. is to be determined. Description of Apparatus: Nicholson's Hydrometer The schematic diagram of a Nicholson hydrometer is shown in Fig. 3.2. It consists of a thin metallic rod with a fixed mark S, connected to a long

About Press Copyright Contact us Creators Advertise Developers Terms Privacy Policy & Safety How YouTube works Test new features NFL Sunday Ticket Press Copyright ...

William Nicholson (13 December 1753 - 21 May 1815) was an English writer, translator, publisher, scientist, inventor, patent agent and civil engineer. He launched the first monthly scientific journal in Britain, Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry, and the Arts, in 1797, and remained its editor until 1814.In 1800, he and Anthony Carlisle were the first to achieve electrolysis, the ...

William Nicholson, born 250 years ago this year, founded a new journal and discovered electrolysis. ... He devised a new hydrometer, worked on industrial machinery and even acted as a water ...

The hydrometer consisted of a sealed tube, with a weight at the bottom to hold the device upright in the water. The rod projecting from the top now bore only a single mark. After weighing the device ...

The specific gravity of the liquid referred to water at the temperature of the experiment is therefore Let the temperature of the water be 15°C.; that of the liquid 11.5°C. Then the specific gravity of liquid at 11.5°C. is 1.078 x 0.99917 = 1.077. Experiments (1) Determine the specific gravity of sulphur by Nicholson's Hydrometer.

The example of Nicholson's Hydrometer at the right is 25 cm high, and is in the Greenslade Collection. William Nicholson (1753-1815) is today best remembered as the founder, in 1797, of the Journal of Natural Philosophy, Chemistry and the Arts, more commonly known as Nicholson's Journal.This he carried on until shortly before his death.

The Nicholson hydrometer is used to determine the specific gravity of a material more dense than water. The conical cup at the bottom should have enough lead in it that the cylinder floats upright in the water. An index mark is made on the the floating tube above the water level. Then three measurements are made: (1) weights are added to the ...