- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to c. 500 AD)

- Medieval History

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- Investing Books

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST NOVELS 2024

- BEST FICTION 2023

- New Literary Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Books for Toddlers and Babies

- Books for Preschoolers

- Books for Kids Age 6-8

- Books for Kids Age 9-12

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2024

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2024

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2024

- Best Kids' Books of 2024

- Mystery & Crime

- Travel Writing

- New History Books

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- NBCC Awards (biography & memoir)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

- Wilbur Smith Prize (adventure)

Make Your Own List

Nonfiction Books » Art » Art History

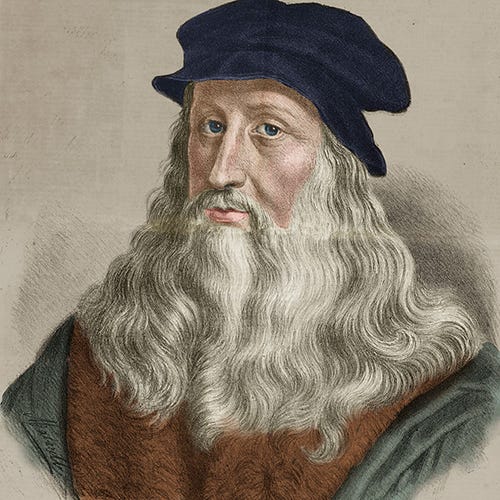

The best books on leonardo da vinci, recommended by martin kemp.

Mona Lisa. The People and the Painting by Martin Kemp

Every generation has its own Leonardo, and for many he remains a man of mystery. Martin Kemp , Emeritus Professor in Art History at Oxford and the author of Mona Lisa: The People and the Painting, helps us identify the non-mythical Leonardo. What might Leonardo be doing were he alive today, in our own digital age?

Interview by Romas Viesulas

The Divine Comedy: Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso by Dante Alighieri

Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation by E.H. Gombrich

Leonardo da Vinci: i documenti e le testimonianze contemporanee by Edoardo Villata

The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci by Jean Paul Richter

Leonardo da Vinci by Kenneth Clark

1 The Divine Comedy: Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso by Dante Alighieri

2 art and illusion: a study in the psychology of pictorial representation by e.h. gombrich, 3 leonardo da vinci: i documenti e le testimonianze contemporanee by edoardo villata, 4 the literary works of leonardo da vinci by jean paul richter, 5 leonardo da vinci by kenneth clark.

F irstly, congratulations on your Leonardo da Vinci book in collaboration with Giuseppe Pallanti. The press release announces boldly that we’re to learn the secrets at the heart of the world’s most iconic work of art. Of course, an air of mystery is perhaps fitting for a book with a subject like Leonardo da Vinci, whose life and work are suffused with myth and speculation. And yet, almost as a final punctuation in your closing paragraph, you state that “There is one Mona Lisa. It was painted by Leonardo. And it is in the Louvre ”. I love this passage! Which summarises so well the spirit of the book. The facts speak for themselves, and they lead us to some very grounded conclusions about the painting, and also about Leonardo.

There is also an important element of mystery which is embedded in the picture, that is to say the ultimate unknowingness of the beloved woman. There Leonardo’s technique induces a sense that we think we can see more than we can. We, then, as viewers, fill it in. There’s this genuine sense that he is leaving something intangible, ineffable, unsaid. So, there is a genuine element of mystery which he has contrived.

The fact that the Mona Lisa in some ways was the product of an unspectacular, almost mundane middle class Renaissance milieu, makes the cultural phenomenon of the painting that much more remarkable. This relatively humble soil was able to give root to this extraordinary flower. In reading the book, I found myself thinking that you could say something similar about Leonardo da Vinci himself.

The portrait is extraordinary because, at that time particularly, portraits were portraits. They were of interest inherently because of the value, status or public profile of the person who is being portrayed. So, to have this sort of painting of a bourgeois woman and for it to become famous almost immediately is extraordinary.

“There’s this genuine sense that he is leaving something intangible, ineffable, unsaid”

Let’s turn to the reading list for our discussion of a ‘non-mythical’ Leonardo. To set the stage, let’s begin with a compatriot of his. Why is Dante important for us to understand Leonardo’s art, and perhaps his scholarly and scientific work as well?

I think Dante is of importance to Leonardo in two respects. One is a fairly obvious one in that he really set in train – not wholly individually but he gave a great impetus to – the standard Florentine poetic genre of the beloved lady. In his work, Beatrice is never really somebody he knows that well but she is idealised and sublimated into this extraordinary object of rarefied desire. He set in motion a tradition that goes through Petrarch and beyond, and one that was still thriving in the Leonardo courts.

As we know, poets wrote about Leonardo’s portraits using this language. So, that Dantesque figure of the beloved lady goes into a Leonardo portrait and then is extracted – as it were – by the poets who were writing about Leonardo. It’s not been noticed very much before but it is obvious to the close observer.

The other aspect to it is that Dante is the supreme poet-natural philosopher. We know about Dante’s imagination, we know his great storytelling abilities, but we tend to take into account rather less that in The Divine Comedy and in all his works – the Convivio (the Banquet) not least – there is an enormous amount of learning about objects, about physics, about the behaviour of things in the natural world and about light, above all. The Paradiso is about light. And also about the act of seeing.

Natural philosophy as a precursor to what we would regard as hard science ….That leads quite naturally to a discussion of E.H. Gombrich’s Art & Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (1960) where he discusses art as a sort of experimental process – an iterative and improvised pursuit – that seems to echo what you’ve described as Dante’s marrying of poetry and science : the transformation of knowledge into poetic vision.

Absolutely. Gombrich was kind of mentor of mine; I never studied with him but he was always immensely encouraging. There are a number of people who are pressing on with art-science agendas and who are interested – both historically and in contemporary terms – with issues of seeing and knowing, which lie behind Gombrich’s The Story of Art . It’s the fact that you don’t just see things and know what they are; you have to have a hypothetical framework, you have to have an interpretive framework, to get leverage on the world. That was very important. I trained as scientist so, in a sense, I knew about hypotheses but less about the philosophical underpinnings which meant that the standard notion of empiricism wouldn’t do the job, that you need schemata models, you need a framework that you can then modify heroically.

“You don’t just see things and know what they are; you have to have an interpretive framework, to get leverage on the world”

For Gombrich, Leonardo was the historical embodiment of that process. He was somebody who had this amazing stock of schemas inherited from the art which he knew but an extraordinary ability to work with the grit of observation and the imagination to see that the old wisdom needed challenging, both on grounds of empirical testing but also on grounds of theoretical constructions. In Gombrich’s “making and matching” formula, there’s the idea that you basically have a way of portraying things; if I wanted to paint a portrait of your face, I have a series of pictorial motifs that I can use and combine to do it. “Matching”, then, is the process which is non-obvious and much more difficult than people realise: to make your eye look like your eye, rather than the general eye which I know how to draw.

If you read Gombrich’s writings – The Story of Art not least but other essays of his as well – then Leonardo is like the light cavalry. When Gombrich gets into a difficult area of argument, then the Leonardo light cavalry come racing over the hill towards the enemy to win the argument.

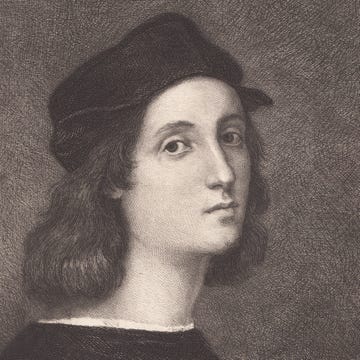

Importantly for me, Gombrich also gave a sanction for looking at non-art as being as profound as high art in terms of its potential analysis. He would put an advertisement for a rotary shaver beside Raphael’s Madonna della sedia because they’re both using rounds. That sounds trivial but he makes a lot of it. So, that ability to fashion a visual history rather than more restrictedly an art history is of immense importance, and is very much in the spirit of Leonardo’s endeavour.

If we consider the way that the framework is deployed to make sense of and accentuate the aesthetic qualities of our experienced environment, some would argue that this is what sets Leonardo apart from a long lineage of extremely talented and extremely visionary artists. Would you say that’s one reason why he’s had such lasting influence and importance?

I think he tries to embed in painting all the knowledge – this extraordinary wide ranging encyclopaedic knowledge which he gleans. He wants painting to be a recreation of the visual world on the basis of this encyclopaedic understanding. Ultimately, it’s an unrealisable dream. Even film and moving images can’t do everything. One of the difficulties he had with finishing paintings, is that the ultimate ambition to make the painting into a universal picture, to carry all this immense baggage of knowledge and fantasy, is in a way unrealisable. There’s a kind of unrealistic aspect to the agenda which is always recognisable with Leonardo.

“He wants painting to be a recreation of the visual world on the basis of this encyclopaedic understanding. Ultimately, it’s an unrealisable dream.”

Under Gombrich’s rubric, the culture informs artistic production. So we stand to learn a lot about Leonardo’s milieu in reading from primary sources. The books you’ve chosen are Jean Paul Richter’s The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci (1883) , and Edoardo Villata’s Leonardo da Vinci – i documenti e le testimonianze contemporanee (1999) . Why these two compendia specifically, when the Leonardo scholarship is so vast? Even the primary source material is sprawling, and not even all of Leonardo’s notebooks have survived.

I always emphasise primary sources. If you teach Leonardo, you are faced with this enormous amount of material. My Leonardo library is too big for my house; it’s in the research hall of the history faculty, and there are bigger libraries than that obviously in professional libraries. So, what do you do? The answer, for me, is go to the primary sources as your first port of call: get a sense of them, naturalise yourself in this extraordinary ability he has to cross boundaries, to move fluidly from the motion of hair to the motion of water and so on, and get a feel for that.

Obviously, you need to have an interpretive framework. Historians and accounts that one can recommend range from something like Kenneth Clark’s very beautiful biography which is about Leonardo as an artist – it doesn’t do more than that – to works which tackle different aspects of his intellectual legacy. What has tended to be missing, at least when I did my first synoptic book on Leonardo da Vinci, was a synthetic gathering together of all these things.

Are there particular segments or chapters or letters that provide a unique insight or summary understanding of who Leonardo was and what made him tick?

It is a tough one but let’s do three passages from the Richter book. One is the letter Leonardo wrote to Ludovico Sforza – Ludovico il Moro, the ruler of Milan – and he’s selling his services. This is a draft letter, it presumably went in a fairer copy to Ludovico, but he details all the military things he can do. He can build bridges for crossing moats and he can dig tunnels and he can construct weapons the sort of which are outside the common usage, as he puts it. It gives an idea of this slightly crazy ambition that he has.

At the end, he says by the way, also in sculpture and painting, I can do things as well as anyone else can and will be happy to do the equestrian memorial – the rider on the horse – for your father which I happen to know you want doing . That’s a flavour of the man who was insanely ambitious, very willing to promote himself and recognised he was special. But it’s endearing, this sheer enthusiasm of listing all the different things that he can do, as though he can’t get it out fast enough.

“What is the core of this person’s artistic personality? And how far is it common across all this enormous range of diverse pursuits?”

The second one would be something from the “Paragone” – the comparison between the arts. This was a set piece debate he indulged in at the court of Ludovico il Moro in Milan. It was a kind of courtly knockabout dispute between poets, musicians, sculptors, painters, and writers more generally. And he was very rude about poetry. It was a serious challenge: they were challenging for the attention of the duke, challenging for prestige in the court, and they were challenging for salaries. And Leonardo is determined to give poetry a tough time.

He parades these arguments – some of them really pretty tenuous – and ultimately comes down to the assertion that the ear is not as good as the eye. The eye is the great vehicle through which we see the world and it’s the primary sense. He then assigns a descriptive role to poetry and says that poetry cannot describe a battle as well as a painting can. Which if taken as a visual description, is undebatable. But is poetry really about visual description? So, that gives you a sense of Leonardo in a court: very brilliant, very agile, and willing to bend the evidence rather creatively in his direction and to his advantage.

The other passage would be one of the later writings ‘On the Eye’ from Manuscript D which is the in the Institute de France. I’m not going to give you a specific passage – they are quite a number of them – and the Richter volumes have very brilliant indices, so you can go and see where the Manuscript D Dell’occhio (‘On the Eye’) is. That is relatively well into his career, it is around 1507-1508, and he was to die in 1519. It deals with the complexities of seeing. There is geometry out there, and he is in thrall to geometry. Mathematics , but above all geometry, is the key to understanding the universe, much like Galileo said “the book of nature is written in mathematics”.

For Leonardo, it is written primarily in geometry. So, there’s enormous attention to working out the reflection, refraction, aerial perspectives of objects, and how the atmosphere works and so on. But he says, and this is relatively later in his life, that we have to understand how the eye works in how we see things. The eye, he observes, is optically a very complicated instrument. He doesn’t have a focussing lens which limits what he can accomplish with his explanation. Before Kepler in the early 17th century, there’s no sense of the lens as an active focussing device. So, he tries to work out how the components of the eye – the humours as they were called: the aqueous humour, the liquid stuff, and the crystalline humour or more gelatinous stuff like the lens in particular – how these combine to create the optics to get an image.

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount .

Most people would think of Leonardo principally as an artist – famous for the Mona Lisa amongst other works – but he seemed to have been quite scathing not only about poets but also his painterly rivals. While most praise was reserved for architects who, I suppose, were the civil scientists of the age. Your own research has been about the relationship between scientific visions of nature and how these are applied to art in practice. In the book Leonardo da Vinci Kenneth Clark describes at length and in very graceful language Leonardo’s constant negotiation between science and symbolism. This monograph was first published in 1939. This is still a canonical work for you in Leonardo studies?

Yes. Leonardo da Vinci is a beautiful book. And Leonardo has been fortunate in some of the writers who have tackled him, like Walter Pater and like Théophile Gautier in France. He has attracted some fine pens to write about him. Kenneth Clark is up there with them. In terms of art history, Clark is rather sniffily regarded by academics. He’s been called Lord Clark of Civilisation because of his famous television series. He has also written Landscape into Art and The Nude which he saw as very much about the intellectual history of art. They’re regarded as popularising. Now, for me, communicating in a broader framework is terrific and to do it as well as Clark is wonderful. But there is a natural sniffiness amongst academics when he rides roughshod over some beloved subtleties that they hold dear.

The book as a whole conveys wonderful shape to Leonardo’s art and life. And Clark is more right about aspects of his science and engineering than he has any right to be. He kept clear of the science, he didn’t really tackle it head on, yet via the art and via the drawings, he gets an enormous amount right about Leonardo’s scientific opus. There’s also his great catalogue, which he did before the monograph, of the drawings at Windsor Castle which holds the greatest set of Leonardo drawings. Most of the anatomical drawings for example are at Windsor.

If you look at what he says about them, even when he doesn’t really deal with the science, he gets things extraordinarily right by intuition. Clark had that instinctive penetration into how Leonardo worked even when he was short of detailed knowledge of the area that he was looking at. To me, that’s a testimony of a certain kind of intuitive insight; having got a toehold Leonardo’s art, he was able to make more of the rest of Leonardo’s work than he really should have been able to do.

At one point, he writes that “there is a Leonardo for every generation”. In Leonardo’s approach to science and art, and the interrelation of the two, could Leonardo’s oeuvre be seen as an antidote to some of the very reductionist thinking that characterises many disciplines, compartmentalisation in the academy, and even in the ways that our daily lives seem to have become hyper-specialised? Do we need to recover this Renaissance notion of the interconnectedness of human knowledge, be it scientific, aesthetic, or otherwise?

Absolutely, yes. He was a lateral thinker to a kind of pathological degree. He couldn’t be contained in an area without seeing its implications for other areas. But it has to be done on a different basis now. In Leonardo’s era, though you couldn’t know everything about everything, this universal knowledge – that is to say, understanding the rudiments of physics, optics, anatomy and so on – could potentially be understood to an effective level by someone with Leonardo’s ambitions. And he wasn’t the only person who aimed at universal understanding. Roger Bacon in the middle ages was the Doctor Mirabilis who aspired to universal wisdom.

A theory has been advanced that the last human to have known everything – to have grasped all knowledge – was Goethe . Since then, the production of knowledge has outstripped our ability to digest and retain it.

Yes, Goethe is a supreme manifestation of that ability to work across boundaries and, indeed, to make your understanding of one area stronger because you’ve really got a sense of what is analogous elsewhere. Hermann von Helmholtz, the nineteenth-century physicist and physiologist is rather good as well and rather underrated. We should at least be able to understand what is going on in other areas, even if we can’t be experts on them.

“Leonardo was a lateral thinker to a kind of pathological degree. He couldn’t be contained in an area without seeing its implications for other areas”

I reviewed a book on quantum mechanics for the Times Literary Supplement which, in a sense, is barmy but it was about the beauty of quantum mechanics. Could I teach students about quantum mechanics? Perhaps not in ways that would be conducive to work in the laboratory. However, I would argue that whatever the discipline, we should know the nature of the enterprise: what kind of thing is going on, what criteria are being used, and so on.

Above all, in terms of Leonardo’s search for universal knowledge, he relies upon a profound respect for the orders of nature and how nature works. He doesn’t see us as separate from that natural world. We are in our bodies. As a microcosm, we embody the nature of the wider world. We are locked into its imperatives, and into how nature works. If you’re a canal engineer and you’re trying to alter the flow of rivers, the way to do it is to work in a friendly and cooperative way with the nature of water, rather than trying to push it around.

Leonardo has a profound respect for the order of nature and the human being’s integral place in that. There is a big message here, which is embedded in that notion of trying to get a universal understanding of how nature works.

In an age where our access to and perception of the world is increasingly being mediated by silicon and glass and software, what place is there for a da Vincian method?

Since we did Leonardo show at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1989, I’ve been immensely interested in getting Leonardo to talk to computers, not just as a database but in thinking how can we effectively put computers in dialogue with Leonardo. If you look at Leonardo’s drawings, he clearly wanted them to move. There’s a clearly an inherent sense of animation. For our show at the V&A, I worked with a very brilliant animator called Steve Maher and we animated some of Leonardo’s drawings to tremendous effect. We found that some of his serial drawings – drawings of serial movement – just needed smoothing out; he got the key stages.

“If you look at Leonardo’s drawings, he clearly wanted them to move. There’s a clearly an inherent sense of animation”

For 2019, I’m talking further to Steve for the five hundredth anniversary of Leonardo’s death about doing a virtual reality reconstruction of aspects of Leonardo. Now, that doesn’t mean to say that he anticipated computer graphics or whatever, but it’s a question of what is inherent in his work and how it can be put into a dialogue with the new media, which he would have been completely sold on. This is not – I hope – an anachronistic enterprise. We are always looking back. We also have to be careful as historians that we’re not manipulating the historic Leonardo and coming up with something which is simply a mirror of our own time. But, provided we’re responsible about that dialogue, then I think it can be immensely stimulating and good public communication as well.

So, very much a Renaissance man for the digital age as well?

People often ask me what would Leonardo be doing if he were around at the moment? which is unanswerable in a way. I say he would certainly be in moving media. He would be doing something with images that move and with virtual reality. He would have been spectacularly impressed with that.

June 8, 2017

Also recommended on Five Books :

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Martin Kemp

Martin Kemp FBA is Emeritus Professor in the History of Art at Trinity College, Oxford University. One of the world's leading authorities on Leonardo da Vinci, he has published extensively on his life and work, including the prize-winning Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man (2006) and Leonardo (2004), La Bella Principessa (2010), written with Pascal Cotte and, most recently, Mona Lisa: The People and the Painting , with Giuseppe Pallanti (2017).

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci was a Renaissance artist and engineer, known for paintings like "The Last Supper" and "Mona Lisa,” and for inventions like a flying machine.

(1452-1519)

Who Was Leonardo da Vinci?

Leonardo da Vinci was a Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, inventor, military engineer and draftsman — the epitome of a true Renaissance man. Gifted with a curious mind and a brilliant intellect, da Vinci studied the laws of science and nature, which greatly informed his work. His drawings, paintings and other works have influenced countless artists and engineers over the centuries.

Da Vinci was born in a farmhouse outside the village of Anchiano in Tuscany, Italy (about 18 miles west of Florence) on April 15, 1452.

Born out of wedlock to respected Florentine notary Ser Piero and a young peasant woman named Caterina, da Vinci was raised by his father and his stepmother.

At the age of five, he moved to his father’s estate in nearby Vinci (the town from which his surname derives), where he lived with his uncle and grandparents.

Young da Vinci received little formal education beyond basic reading, writing and mathematics instruction, but his artistic talents were evident from an early age.

Around the age of 14, da Vinci began a lengthy apprenticeship with the noted artist Andrea del Verrocchio in Florence. He learned a wide breadth of technical skills including metalworking, leather arts, carpentry, drawing, painting and sculpting.

His earliest known dated work — a pen-and-ink drawing of a landscape in the Arno valley — was sketched in 1473.

Early Works

At the age of 20, da Vinci qualified for membership as a master artist in Florence’s Guild of Saint Luke and established his own workshop. However, he continued to collaborate with del Verrocchio for an additional five years.

It is thought that del Verrocchio completed his “Baptism of Christ” around 1475 with the help of his student, who painted part of the background and the young angel holding the robe of Jesus.

According to Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects , written around 1550 by artist Giorgio Vasari, del Verrocchio was so humbled by the superior talent of his pupil that he never picked up a paintbrush again. (Most scholars, however, dismiss Vasari’s account as apocryphal.)

In 1478, after leaving del Verrocchio’s studio, da Vinci received his first independent commission for an altarpiece to reside in a chapel inside Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio.

Three years later the Augustinian monks of Florence’s San Donato a Scopeto tasked him to paint “Adoration of the Magi.” The young artist, however, would leave the city and abandon both commissions without ever completing them.

Was Leonardo da Vinci Gay?

Many historians believe that da Vinci was a homosexual: Florentine court records from 1476 show that da Vinci and four other young men were charged with sodomy, a crime punishable by exile or death.

After no witnesses showed up to testify against 24-year-old da Vinci, the charges were dropped, but his whereabouts went entirely undocumented for the following two years.

Several other famous Florentine artists were also known to have been homosexual, including Michelangelo , Donatello and Sandro Botticelli . Indeed, homosexuality was such a fact of artistic life in Renaissance Florence that the word "florenzer" became German slang for “gay.”

Leonardo da Vinci: Paintings

Although da Vinci is known for his artistic abilities, fewer than two dozen paintings attributed to him exist. One reason is that his interests were so varied that he wasn’t a prolific painter. Da Vinci’s most famous works include the “Vitruvian Man,” “The Last Supper” and the “ Mona Lisa .”

Vitruvian Man

Art and science intersected perfectly in da Vinci’s sketch of “Vitruvian Man,” drawn in 1490, which depicted a nude male figure in two superimposed positions with his arms and legs apart inside both a square and a circle.

The now-famous sketch represents da Vinci's study of proportion and symmetry, as well as his desire to relate man to the natural world.

The Last Supper

Around 1495, Ludovico Sforza, then the Duke of Milan, commissioned da Vinci to paint “The Last Supper” on the back wall of the dining hall inside the monastery of Milan’s Santa Maria delle Grazie.

The masterpiece, which took approximately three years to complete, captures the drama of the moment when Jesus informs the Twelve Apostles gathered for Passover dinner that one of them would soon betray him. The range of facial expressions and the body language of the figures around the table bring the masterful composition to life.

The decision by da Vinci to paint with tempera and oil on dried plaster instead of painting a fresco on fresh plaster led to the quick deterioration and flaking of “The Last Supper.” Although an improper restoration caused further damage to the mural, it has now been stabilized using modern conservation techniques.

In 1503, da Vinci started working on what would become his most well-known painting — and arguably the most famous painting in the world —the “Mona Lisa.” The privately commissioned work is characterized by the enigmatic smile of the woman in the half-portrait, which derives from da Vinci’s sfumato technique.

Adding to the allure of the “Mona Lisa” is the mystery surrounding the identity of the subject. Princess Isabella of Naples, an unnamed courtesan and da Vinci’s own mother have all been put forth as potential sitters for the masterpiece. It has even been speculated that the subject wasn’t a female at all but da Vinci’s longtime apprentice Salai dressed in women’s clothing.

Based on accounts from an early biographer, however, the "Mona Lisa" is a picture of Lisa del Giocondo, the wife of a wealthy Florentine silk merchant. The painting’s original Italian name — “La Gioconda” — supports the theory, but it’s far from certain. Some art historians believe the merchant commissioned the portrait to celebrate the pending birth of the couple’s next child, which means the subject could have been pregnant at the time of the painting.

If the Giocondo family did indeed commission the painting, they never received it. For da Vinci, the "Mona Lisa" was forever a work in progress, as it was his attempt at perfection, and he never parted with the painting. Today, the "Mona Lisa" hangs in the Louvre Museum in Paris, France, secured behind bulletproof glass and regarded as a priceless national treasure seen by millions of visitors each year.

Battle of Anghiari

In 1503, da Vinci also started work on the "Battle of Anghiari," a mural commissioned for the council hall in the Palazzo Vecchio that was to be twice as large as "The Last Supper."

He abandoned the "Battle of Anghiari" project after two years when the mural began to deteriorate before he had a chance to finish it.

In 1482, Florentine ruler Lorenzo de' Medici commissioned da Vinci to create a silver lyre and bring it as a peace gesture to Ludovico Sforza. After doing so, da Vinci lobbied Ludovico for a job and sent the future Duke of Milan a letter that barely mentioned his considerable talents as an artist and instead touted his more marketable skills as a military engineer.

Using his inventive mind, da Vinci sketched war machines such as a war chariot with scythe blades mounted on the sides, an armored tank propelled by two men cranking a shaft and even an enormous crossbow that required a small army of men to operate.

The letter worked, and Ludovico brought da Vinci to Milan for a tenure that would last 17 years. During his time in Milan, da Vinci was commissioned to work on numerous artistic projects as well, including “The Last Supper.”

Da Vinci’s ability to be employed by the Sforza clan as an architecture and military engineering advisor as well as a painter and sculptor spoke to da Vinci’s keen intellect and curiosity about a wide variety of subjects.

Flying Machine

Always a man ahead of his time, da Vinci appeared to prophesy the future with his sketches of devices that resemble a modern-day bicycle and a type of helicopter.

Perhaps his most well-known invention is a flying machine, which is based on the physiology of a bat. These and other explorations into the mechanics of flight are found in da Vinci's Codex on the Flight of Birds, a study of avian aeronautics, which he began in 1505.

Like many leaders of Renaissance humanism, da Vinci did not see a divide between science and art. He viewed the two as intertwined disciplines rather than separate ones. He believed studying science made him a better artist.

In 1502 and 1503, da Vinci also briefly worked in Florence as a military engineer for Cesare Borgia, the illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI and commander of the papal army. He traveled outside of Florence to survey military construction projects and sketch city plans and topographical maps.

He designed plans, possibly with noted diplomat Niccolò Machiavelli , to divert the Arno River away from rival Pisa in order to deny its wartime enemy access to the sea.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S LEONARDO DA VINCI FACT CARD

Da Vinci’s Study of Anatomy and Science

Da Vinci thought sight was humankind’s most important sense and eyes the most important organ, and he stressed the importance of saper vedere, or “knowing how to see.” He believed in the accumulation of direct knowledge and facts through observation.

“A good painter has two chief objects to paint — man and the intention of his soul,” da Vinci wrote. “The former is easy, the latter hard, for it must be expressed by gestures and the movement of the limbs.”

To more accurately depict those gestures and movements, da Vinci began to study anatomy seriously and dissect human and animal bodies during the 1480s. His drawings of a fetus in utero, the heart and vascular system, sex organs and other bone and muscular structures are some of the first on human record.

In addition to his anatomical investigations, da Vinci studied botany, geology, zoology, hydraulics, aeronautics and physics. He sketched his observations on loose sheets of papers and pads that he tucked inside his belt.

Da Vinci placed the papers in notebooks and arranged them around four broad themes—painting, architecture, mechanics and human anatomy. He filled dozens of notebooks with finely drawn illustrations and scientific observations.

Ludovico Sforza also tasked da Vinci with sculpting a 16-foot-tall bronze equestrian statue of his father and founder of the family dynasty, Francesco Sforza. With the help of apprentices and students in his workshop, da Vinci worked on the project on and off for more than a dozen years.

Da Vinci sculpted a life-size clay model of the statue, but the project was put on hold when war with France required bronze to be used for casting cannons, not sculptures. After French forces overran Milan in 1499 — and shot the clay model to pieces — da Vinci fled the city along with the duke and the Sforza family.

Ironically, Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, who led the French forces that conquered Ludovico in 1499, followed in his foe’s footsteps and commissioned da Vinci to sculpt a grand equestrian statue, one that could be mounted on his tomb. After years of work and numerous sketches by da Vinci, Trivulzio decided to scale back the size of the statue, which was ultimately never finished.

Final Years

Da Vinci returned to Milan in 1506 to work for the very French rulers who had overtaken the city seven years earlier and forced him to flee.

Among the students who joined his studio was young Milanese aristocrat Francesco Melzi, who would become da Vinci’s closest companion for the rest of his life. He did little painting during his second stint in Milan, however, and most of his time was instead dedicated to scientific studies.

Amid political strife and the temporary expulsion of the French from Milan, da Vinci left the city and moved to Rome in 1513 along with Salai, Melzi and two studio assistants. Giuliano de’ Medici, brother of newly installed Pope Leo X and son of his former patron, gave da Vinci a monthly stipend along with a suite of rooms at his residence inside the Vatican.

His new patron, however, also gave da Vinci little work. Lacking large commissions, he devoted most of his time in Rome to mathematical studies and scientific exploration.

After being present at a 1515 meeting between France’s King Francis I and Pope Leo X in Bologna, the new French monarch offered da Vinci the title “Premier Painter and Engineer and Architect to the King.”

Along with Melzi, da Vinci departed for France, never to return. He lived in the Chateau de Cloux (now Clos Luce) near the king’s summer palace along the Loire River in Amboise. As in Rome, da Vinci did little painting during his time in France. One of his last commissioned works was a mechanical lion that could walk and open its chest to reveal a bouquet of lilies.

How Did Leonardo da Vinci Die?

Da Vinci died of a probable stroke on May 2, 1519, at the age of 67. He continued work on his scientific studies until his death; his assistant, Melzi, became the principal heir and executor of his estate. The “Mona Lisa” was bequeathed to Salai.

For centuries after his death, thousands of pages from his private journals with notes, drawings, observations and scientific theories have surfaced and provided a fuller measure of the true "Renaissance man."

Book and Movie

Although much has been written about da Vinci over the years, Walter Isaacson explored new territory with an acclaimed 2017 biography, Leonardo da Vinci , which offers up details on what drove the artist's creations and inventions.

The buzz surrounding the book carried into 2018, with the announcement that it had been optioned for a big-screen adaptation starring Leonardo DiCaprio .

Salvator Mundi

In 2017, the art world was sent buzzing with the news that the da Vinci painting "Salvator Mundi" had been sold at a Christie's auction to an undisclosed buyer for a whopping $450.3 million. That amount dwarfed the previous record for an art work sold at an auction, the $179.4 million paid for “Women of Algiers" by Pablo Picasso in 2015.

The sales figure was stunning in part because of the damaged condition of the oil-on-panel, which features Jesus Christ with his right hand raised in blessing and his left holding a crystal orb, and because not all experts believe it was rendered by da Vinci.

However, Christie's had launched what one dealer called a "brilliant marketing campaign," which promoted the work as "the holy grail of our business" and "the last da Vinci." Prior to the sale, it was the only known painting by the old master still in a private collection.

The Saudi Embassy stated that Prince Bader bin Abdullah bin Mohammed bin Farhan al-Saud of Saudi Arabia had acted as an agent for the ministry of culture of Abu Dhabi, in the United Arab Emirates. Around that time, the newly-opened Louvre Abu Dhabi announced that the record-breaking artwork would be exhibited in its collection.

Michelangelo

"],["

Vincent van Gogh

"]]" tml-render-layout="inline">

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Leonardo da Vinci

- Birth Year: 1452

- Birth date: April 15, 1452

- Birth City: Vinci

- Birth Country: Italy

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Leonardo da Vinci was a Renaissance artist and engineer, known for paintings like "The Last Supper" and "Mona Lisa,” and for inventions like a flying machine.

- Science and Medicine

- Writing and Publishing

- Architecture

- Technology and Engineering

- Astrological Sign: Aries

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Leonardo da Vinci was born out of wedlock to a respected Florentine notary and a young peasant woman.

- Da Vinci used tempera and oil on dried plaster to paint "The Last Supper," which led to its quick deterioration and flaking.

- For da Vinci, the "Mona Lisa" was forever a work in progress, as it was his attempt at perfection, and he never parted with the painting.

- Death Year: 1519

- Death date: May 2, 1519

- Death City: Amboise

- Death Country: France

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Leonardo da Vinci Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/leonardo-da-vincii

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: August 28, 2019

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- Iron rusts from disuse, stagnant water loses its purity and in cold weather becomes frozen; even so does inaction sap the vigor of the mind.

- Nothing is hidden beneath the sun.

- Obstacles cannot bend me. Every obstacle yields to effort.

- We make our life by the death of others.

- Necessity is the mistress and guardian of nature.

- One ought not to desire the impossible.

- He who neglects to punish evil sanctions the doing thereof.

- Darkness is the absence of light. Shadow is the diminution of light.

- The painter who draws by practice and judgment of the eye without the use of reason, is like the mirror that reproduces within itself all the objects which are set opposite to it without knowledge of the same.

- He who does not value life does not deserve it.

- Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.

- Nothing strengthens authority so much as silence.

Famous Painters

Frida Kahlo

Jean-Michel Basquiat

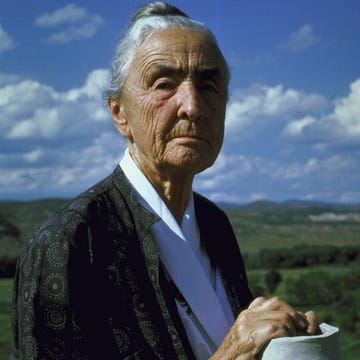

Georgia O'Keeffe

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Leonardo da Vinci

By: History.com Editors

Updated: July 13, 2022 | Original: December 2, 2009

Leonardo da Vinci was a painter, engineer, architect, inventor, and student of all things scientific. His natural genius crossed so many disciplines that he epitomized the term “ Renaissance man.” Today he remains best known for two of his paintings, " Mona Lisa " and "The Last Supper." Largely self-educated, he filled dozens of secret notebooks with inventions, observations and theories about pursuits from aeronautics to human anatomy. His combination of intellect and imagination allowed him to create, at least on paper, such inventions as the bicycle, the helicopter and an airplane based on the physiology and flying ability of a bat.

When Was Leonardo da Vinci Born?

Da Vinci was born in Anchiano, Tuscany (now Italy), in 1452, close to the town of Vinci that provided the surname we associate with him today. In his own time he was known just as Leonardo or as “Il Florentine,” since he lived near Florence—and was famed as an artist, inventor and thinker.

Did you know? Leonardo da Vinci’s father, an attorney and notary, and his peasant mother were never married to one another, and Leonardo was the only child they had together. With other partners, they had a total of 17 other children, da Vinci’s half-siblings.

Da Vinci’s parents weren’t married, and his mother, Caterina, a peasant, wed another man while da Vinci was very young and began a new family. Beginning around age 5, he lived on the estate in Vinci that belonged to the family of his father, Ser Peiro, an attorney and notary. Da Vinci’s uncle, who had a particular appreciation for nature that da Vinci grew to share, also helped raise him.

Early Career

Da Vinci received no formal education beyond basic reading, writing and math, but his father appreciated his artistic talent and apprenticed him at around age 15 to the noted sculptor and painter Andrea del Verrocchio of Florence. For about a decade, da Vinci refined his painting and sculpting techniques and trained in mechanical arts.

When he was 20, in 1472, the painters’ guild of Florence offered da Vinci membership, but he remained with Verrocchio until he became an independent master in 1478. Around 1482, he began to paint his first commissioned work, The Adoration of the Magi, for Florence’s San Donato, a Scopeto monastery.

However, da Vinci never completed that piece, because shortly thereafter he relocated to Milan to work for the ruling Sforza clan, serving as an engineer, painter, architect, designer of court festivals and, most notably, a sculptor.

The family asked da Vinci to create a magnificent 16-foot-tall equestrian statue, in bronze, to honor dynasty founder Francesco Sforza. Da Vinci worked on the project on and off for 12 years, and in 1493 a clay model was ready to display. Imminent war, however, meant repurposing the bronze earmarked for the sculpture into cannons, and the clay model was destroyed in the conflict after the ruling Sforza duke fell from power in 1499.

'The Last Supper'

Although relatively few of da Vinci’s paintings and sculptures survive—in part because his total output was quite small—two of his extant works are among the world’s most well-known and admired paintings.

The first is da Vinci’s “The Last Supper,” painted during his time in Milan, from about 1495 to 1498. A tempera and oil mural on plaster, “The Last Supper” was created for the refectory of the city’s Monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Also known as “The Cenacle,” this work measures about 15 by 29 feet and is the artist’s only surviving fresco. It depicts the Passover dinner during which Jesus Christ addresses the Apostles and says, “One of you shall betray me.”

One of the painting’s stellar features is each Apostle’s distinct emotive expression and body language. Its composition, in which Jesus is centered among yet isolated from the Apostles, has influenced generations of painters.

'Mona Lisa'

When Milan was invaded by the French in 1499 and the Sforza family fled, da Vinci escaped as well, possibly first to Venice and then to Florence. There, he painted a series of portraits that included “La Gioconda,” a 21-by-31-inch work that’s best known today as “Mona Lisa.” Painted between approximately 1503 and 1506, the woman depicted—especially because of her mysterious slight smile—has been the subject of speculation for centuries.

In the past she was often thought to be Mona Lisa Gherardini, a courtesan, but current scholarship indicates that she was Lisa del Giocondo, wife of Florentine merchant Francisco del Giocondo. Today, the portrait—the only da Vinci portrait from this period that survives—is housed at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France, where it attracts millions of visitors each year.

Around 1506, da Vinci returned to Milan, along with a group of his students and disciples, including young aristocrat Francesco Melzi, who would be Leonardo’s closest companion until the artist’s death. Ironically, the victor over the Duke Ludovico Sforza, Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, commissioned da Vinci to sculpt his grand equestrian-statue tomb. It, too, was never completed (this time because Trivulzio scaled back his plan). Da Vinci spent seven years in Milan, followed by three more in Rome after Milan once again became inhospitable because of political strife.

Inventions and Philosophy

Da Vinci’s interests ranged far beyond fine art. He studied nature, mechanics, anatomy, physics, architecture, weaponry and more, often creating accurate, workable designs for machines like the bicycle, helicopter, submarine and military tank that would not come to fruition for centuries. He was, wrote Sigmund Freud, “like a man who awoke too early in the darkness, while the others were all still asleep.”

Several themes could be said to unite da Vinci’s eclectic interests. Most notably, he believed that sight was mankind’s most important sense and that “saper vedere” (“knowing how to see”) was crucial to living all aspects of life fully. He saw science and art as complementary rather than distinct disciplines, and thought that ideas formulated in one realm could—and should—inform the other.

Probably because of his abundance of diverse interests, da Vinci failed to complete a significant number of his paintings and projects. He spent a great deal of time immersing himself in nature, testing scientific laws, dissecting bodies (human and animal) and thinking and writing about his observations.

Da Vinci’s Notebooks

At some point in the early 1490s, da Vinci began filling notebooks related to four broad themes—painting, architecture, mechanics and human anatomy—creating thousands of pages of neatly drawn illustrations and densely penned commentary, some of which (thanks to left-handed “mirror script”) was indecipherable to others.

The notebooks—often referred to as da Vinci’s manuscripts and “codices”—are housed today in museum collections after having been scattered after his death. The Codex Atlanticus, for instance, includes a plan for a 65-foot mechanical bat, essentially a flying machine based on the physiology of the bat and on the principles of aeronautics and physics.

Other notebooks contained da Vinci’s anatomical studies of the human skeleton, muscles, brain, and digestive and reproductive systems, which brought new understanding of the human body to a wider audience. However, because they weren’t published in the 1500s, da Vinci’s notebooks had little influence on scientific advancement in the Renaissance period.

How Did Leonardo da Vinci Die?

Da Vinci left Italy for good in 1516, when French ruler Francis I generously offered him the title of “Premier Painter and Engineer and Architect to the King,” which afforded him the opportunity to paint and draw at his leisure while living in a country manor house, the Château of Cloux, near Amboise in France.

Although accompanied by Melzi, to whom he would leave his estate, the bitter tone in drafts of some of his correspondence from this period indicate that da Vinci’s final years may not have been very happy ones. (Melzi would go on to marry and have a son, whose heirs, upon his death, sold da Vinci’s estate.)

Da Vinci died at Cloux (now Clos-Lucé) in 1519 at age 67. He was buried nearby in the palace church of Saint-Florentin. The French Revolution nearly obliterated the church, and its remains were completely demolished in the early 1800s, making it impossible to identify da Vinci’s exact gravesite.

HISTORY Vault: World History

Stream scores of videos about world history, from the Crusades to the Third Reich.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The best books on Leonardo da Vinci picked by Professor Martin Kemp. From the best primary sources to the best biography of this great artist

Leonardo da Vinci was an artist and engineer who is best known for his paintings, notably the Mona Lisa (c. 1503–19) and the Last Supper (1495–98). His drawing of the Vitruvian Man (c. 1490) has also become a cultural icon.

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci [b] (15 April 1452 – 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. [3]

Leonardo da Vinci was a Renaissance painter, sculptor, architect, inventor, military engineer and draftsman — the epitome of a true Renaissance man. Gifted with a curious mind and a brilliant...

Leonardo da Vinci was a painter, engineer, architect, inventor, and student of all things scientific. His natural genius crossed so many disciplines that he epitomized the term “ Renaissance...

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was an Italian Renaissance artist, architect, engineer, and scientist. He is renowned for his ability to observe and capture nature, scientific phenomena, and human emotions in all media .