- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Pavlov's Dogs and the Discovery of Classical Conditioning

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Sean is a fact-checker and researcher with experience in sociology, field research, and data analytics.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Sean-Blackburn-1000-a8b2229366944421bc4b2f2ba26a1003.jpg)

Jules Clark/Getty Images

- Pavlov's Theory

Pavlov's dog experiments played a critical role in the discovery of one of the most important concepts in psychology: Classical conditioning .

While it happened quite by accident, Pavlov's famous experiments had a major impact on our understanding of how learning takes place as well as the development of the school of behavioral psychology. Classical conditioning is sometimes called Pavlovian conditioning.

Pavlov's Dog: A Background

How did experiments on the digestive response in dogs lead to one of the most important discoveries in psychology? Ivan Pavlov was a noted Russian physiologist who won the 1904 Nobel Prize for his work studying digestive processes.

While studying digestion in dogs, Pavlov noted an interesting occurrence: His canine subjects would begin to salivate whenever an assistant entered the room.

The concept of classical conditioning is studied by every entry-level psychology student, so it may be surprising to learn that the man who first noted this phenomenon was not a psychologist at all.

In his digestive research, Pavlov and his assistants would introduce a variety of edible and non-edible items and measure the saliva production that the items produced.

Salivation, he noted, is a reflexive process. It occurs automatically in response to a specific stimulus and is not under conscious control.

However, Pavlov noted that the dogs would often begin salivating in the absence of food and smell. He quickly realized that this salivary response was not due to an automatic, physiological process.

Pavlov's Theory of Classical Conditioning

Based on his observations, Pavlov suggested that the salivation was a learned response. Pavlov's dog subjects were responding to the sight of the research assistants' white lab coats, which the animals had come to associate with the presentation of food.

Unlike the salivary response to the presentation of food, which is an unconditioned reflex, salivating to the expectation of food is a conditioned reflex.

Pavlov then focused on investigating exactly how these conditioned responses are learned or acquired. In a series of experiments, he set out to provoke a conditioned response to a previously neutral stimulus.

He opted to use food as the unconditioned stimulus , or the stimulus that evokes a response naturally and automatically. The sound of a metronome was chosen to be the neutral stimulus.

The dogs would first be exposed to the sound of the ticking metronome, and then the food was immediately presented.

After several conditioning trials, Pavlov noted that the dogs began to salivate after hearing the metronome. "A stimulus which was neutral in and of itself had been superimposed upon the action of the inborn alimentary reflex," Pavlov wrote of the results.

"We observed that, after several repetitions of the combined stimulation, the sounds of the metronome had acquired the property of stimulating salivary secretion."

In other words, the previously neutral stimulus (the metronome) had become what is known as a conditioned stimulus that then provoked a conditioned response (salivation).

To review, the following are some key components used in Pavlov's theory:

- Conditioned stimulus : This is what the neutral stimulus becomes after training (i.e., the metronome was the conditioned stimulus after Pavlov trained the dogs to respond to it)

- Unconditioned stimulus : A stimulus that produces an automatic response (i.e., the food was the unconditioned stimulus because it made the dogs automatically salivate)

- Conditioned response (conditioned reflex) : A learned response to previously neutral stimulus (i.e., the salivation was a conditioned response to the metronome)

- Unconditioned response (unconditioned reflex) : A response that is automatic (i.e., the dog's salivating is an unconditioned response to the food)

Impact of Pavlov's Research

Pavlov's discovery of classical conditioning remains one of the most important in psychology's history.

In addition to forming the basis of what would become behavioral psychology , the classical conditioning process remains important today for numerous applications, including behavioral modification and mental health treatment.

Principles of classical conditioning are used to treat the following mental health disorders:

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Panic attacks and panic disorder

- Substance use disorders

For instance, a specific type of treatment called aversion therapy uses conditioned responses to help people with anxiety or a specific phobia.

A therapist will help a person face the object of their fear gradually—while helping them manage any fear responses that arise. Gradually, the person will form a neutral response to the object.

Pavlov’s work has also inspired research on how to apply classical conditioning principles to taste aversions . The principles have been used to prevent coyotes from preying on domestic livestock and to use neutral stimulus (eating some type of food) paired with an unconditioned response (negative results after eating the food) to create an aversion to a particular food.

Unlike other forms of classical conditioning, this type of conditioning does not require multiple pairings in order for an association to form. In fact, taste aversions generally occur after just a single pairing. Ranchers have found ways to put this form of classical conditioning to good use to protect their herds.

In one example, mutton was injected with a drug that produces severe nausea. After eating the poisoned meat, coyotes then avoided sheep herds rather than attack them.

A Word From Verywell

While Pavlov's discovery of classical conditioning formed an essential part of psychology's history, his work continues to inspire further research today. His contributions to psychology have helped make the discipline what it is today and will likely continue to shape our understanding of human behavior for years to come.

Adams M. The kingdom of dogs: Understanding Pavlov’s experiments as human–animal relationships . Theory & Psychology . 2019;30(1):121-141. doi:10.1177/0959354319895597

Fanselow MS, Wassum KM. The origins and organization of vertebrate Pavlovian conditioning . Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;8(1):a021717. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021717

Nees F, Heinrich A, Flor H. A mechanism-oriented approach to psychopathology: The role of Pavlovian conditioning . Int J Psychophysiol. 2015;98(2):351-364. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.05.005

American Psychological Association. What is exposure therapy?

Lin JY, Arthurs J, Reilly S. Conditioned taste aversions: From poisons to pain to drugs of abuse. Psychon Bull Rev . 2017;24(2):335-351. doi:10.3758/s13423-016-1092-8

Gustafson, C.R., Kelly, D.J, Sweeney, M., & Garcia, J. Prey-lithium aversions: I. Coyotes and wolves. Behavioral Biology. 1976; 17: 61-72.

Hock, R.R. Forty studies that changed psychology: Explorations into the history of psychological research. (4th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson Education; 2002.

- Gustafson, C.R., Garcia, J., Hawkins, W., & Rusiniak, K. Coyote predation control by aversive conditioning. Science. 1974; 184: 581-583.

- Pavlov, I.P. Conditioned reflexes . London: Oxford University Press; 1927.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Classical Conditioning: How It Works With Examples

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Classical conditioning (also known as Pavlovian or respondent conditioning) is learning through association and was discovered by Pavlov , a Russian physiologist. In simple terms, two stimuli are linked together to produce a new learned response in a person or animal.

John B. Watson proposed that the process of classical conditioning (based on Pavlov’s observations) was able to explain all aspects of human psychology.

If you pair a neutral stimulus (NS) with an unconditioned stimulus (US) that already triggers an unconditioned response (UR) that neutral stimulus will become a conditioned stimulus (CS), triggering a conditioned response (CR) similar to the original unconditioned response.

Everything from speech to emotional responses was simply patterns of stimulus and response. Watson completely denied the existence of the mind or consciousness. Watson believed that all individual differences in behavior were due to different learning experiences.

Watson (1924, p. 104) famously said:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select – doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations and the race of his ancestors.

How Classical Conditioning Works

There are three stages of classical conditioning. At each stage, the stimuli and responses are given special scientific terms:

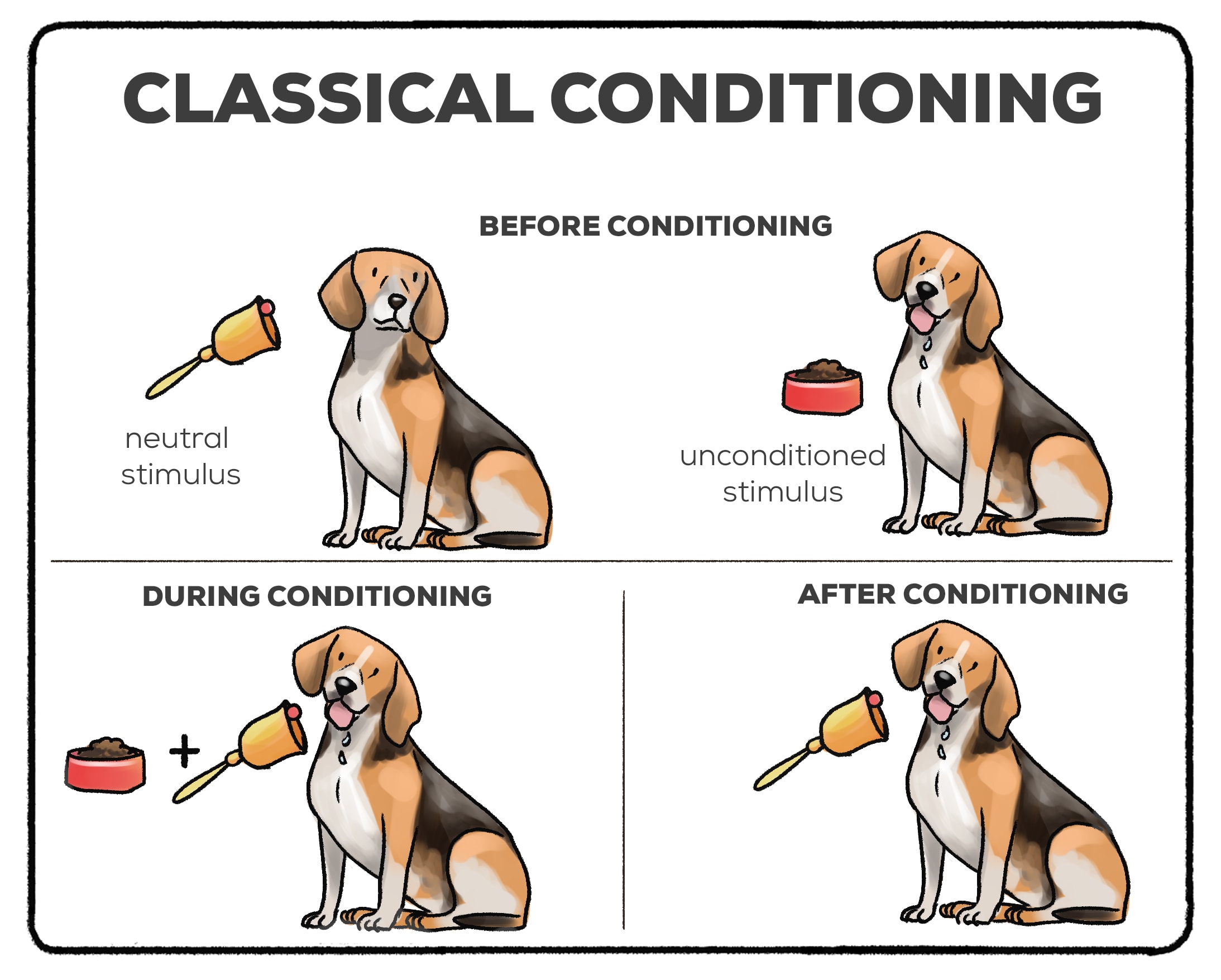

Stage 1: Before Conditioning:

In this stage, the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) produces an unconditioned response (UCR) in an organism.

In basic terms, this means that a stimulus in the environment has produced a behavior/response that is unlearned (i.e., unconditioned) and, therefore, is a natural response that has not been taught. In this respect, no new behavior has been learned yet.

For example, a stomach virus (UCS) would produce a response of nausea (UCR). In another example, a perfume (UCS) could create a response of happiness or desire (UCR).

This stage also involves another stimulus that has no effect on a person and is called the neutral stimulus (NS). The NS could be a person, object, place, etc.

The neutral stimulus in classical conditioning does not produce a response until it is paired with the unconditioned stimulus.

Stage 2: During Conditioning:

During this stage, a stimulus which produces no response (i.e., neutral) is associated with the unconditioned stimulus, at which point it now becomes known as the conditioned stimulus (CS).

For example, a stomach virus (UCS) might be associated with eating a certain food such as chocolate (CS). Also, perfume (UCS) might be associated with a specific person (CS).

For classical conditioning to be effective, the conditioned stimulus should occur before the unconditioned stimulus, rather than after it, or during the same time. Thus, the conditioned stimulus acts as a type of signal or cue for the unconditioned stimulus.

In some cases, conditioning may take place if the NS occurs after the UCS (backward conditioning), but this normally disappears quite quickly. The most important aspect of the conditioning stimulus is the it helps the organism predict the coming of the unconditional stimulus.

Often during this stage, the UCS must be associated with the CS on a number of occasions, or trials, for learning to take place.

However, one trial learning can happen on certain occasions when it is not necessary for an association to be strengthened over time (such as being sick after food poisoning or drinking too much alcohol).

Stage 3: After Conditioning:

The conditioned stimulus (CS) has been associated with the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) to create a new conditioned response (CR).

For example, a person (CS) who has been associated with nice perfume (UCS) is now found attractive (CR). Also, chocolate (CS) which was eaten before a person was sick with a virus (UCS) now produces a response of nausea (CR).

Classical Conditioning Examples

Pavlov’s dogs.

The most famous example of classical conditioning was Ivan Pavlov’s experiment with dogs , who salivated in response to a bell tone. Pavlov showed that when a bell was sounded each time the dog was fed, the dog learned to associate the sound with the presentation of the food.

He first presented the dogs with the sound of a bell; they did not salivate so this was a neutral stimulus. Then he presented them with food, they salivated. The food was an unconditioned stimulus, and salivation was an unconditioned (innate) response.

He then repeatedly presented the dogs with the sound of the bell first and then the food (pairing) after a few repetitions, the dogs salivated when they heard the sound of the bell. The bell had become the conditioned stimulus and salivation had become the conditioned response.

Fear Response

Watson & Rayner (1920) were the first psychologists to apply the principles of classical conditioning to human behavior by looking at how this learning process may explain the development of phobias.

They did this in what is now considered to be one of the most ethically dubious experiments ever conducted – the case of Little Albert . Albert B.’s mother was a wet nurse in a children’s hospital. Albert was described as ‘healthy from birth’ and ‘on the whole stolid and unemotional’.

When he was about nine months old, his reactions to various stimuli (including a white rat, burning newspapers, and a hammer striking a four-foot steel bar just behind his head) were tested.

Only the last of these frightened him, so this was designated the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) and fear the unconditioned response (UCR). The other stimuli were neutral because they did not produce fear.

When Albert was just over eleven months old, the rat and the UCS were presented together: as Albert reached out to stroke the animal, Watson struck the bar behind his head.

This occurred seven times in total over the next seven weeks. By this time, the rat, the conditioned stimulus (CS), on its own frightened Albert, and fear was now a conditioned response (CR).

The CR transferred spontaneously to the rabbit, the dog, and other stimuli that had been previously neutral. Five days after conditioning, the CR produced by the rat persisted. After ten days, it was ‘much less marked’, but it was still evident a month later.

Carter and Tiffany (1999) support the cue reactivity theory, they carried out a meta-analysis reviewing 41 cue-reactivity studies that compared responses of alcoholics, cigarette smokers, cocaine addicts and heroin addicts to drug-related versus neutral stimuli.

They found that dependent individuals reacted strongly to the cues presented and reported craving and physiological arousal.

Panic Disorder

Classical conditioning is thought to play an important role in the development of Pavlov (Bouton et al., 2002).

Panic disorder often begins after an initial “conditioning episode” involving an early panic attack. The panic attack serves as an unconditioned stimulus (US) that gets paired with neutral stimuli (conditioned stimuli or CS), allowing those stimuli to later trigger anxiety and panic reactions (conditioned responses or CRs).

The panic attack US can become associated with interoceptive cues (like increased heart rate) as well as external situational cues that are present during the attack. This allows those cues to later elicit anxiety and possibly panic (CRs).

Through this conditioning process, anxiety becomes focused on the possibility of having another panic attack. This anticipatory anxiety (a CR) is seen as a key step in the development of panic disorder, as it leads to heightened vigilance and sensitivity to bodily cues that can trigger future attacks.

The presence of conditioned anxiety can serve to potentiate or exacerbate future panic attacks. Anxiety cues essentially lower the threshold for panic. This helps explain how panic disorder can spiral after the initial conditioning episode.

Evidence suggests most patients with panic disorder recall an initial panic attack or conditioning event that preceded the disorder. Prospective studies also show conditioned anxiety and panic reactions can develop after an initial panic episode.

Classical conditioning processes are believed to often occur outside of conscious awareness in panic disorder, reflecting the operation of emotional neural systems separate from declarative knowledge systems.

Cue reactivity is the theory that people associate situations (e.g., meeting with friends)/ places (e.g., pub) with the rewarding effects of nicotine, and these cues can trigger a feeling of craving (Carter & Tiffany, 1999).

These factors become smoking-related cues. Prolonged use of nicotine creates an association between these factors and smoking based on classical conditioning.

Nicotine is the unconditioned stimulus (UCS), and the pleasure caused by the sudden increase in dopamine levels is the unconditioned response (UCR). Following this increase, the brain tries to lower the dopamine back to a normal level.

The stimuli that have become associated with nicotine were neutral stimuli (NS) before “learning” took place but they became conditioned stimuli (CS), with repeated pairings. They can produce the conditioned response (CR).

However, if the brain has not received nicotine, the levels of dopamine drop, and the individual experiences withdrawal symptoms therefore is more likely to feel the need to smoke in the presence of the cues that have become associated with the use of nicotine.

Classroom Learning

The implications of classical conditioning in the classroom are less important than those of operant conditioning , but there is still a need for teachers to try to make sure that students associate positive emotional experiences with learning.

If a student associates negative emotional experiences with school, then this can obviously have bad results, such as creating a school phobia.

For example, if a student is bullied at school they may learn to associate the school with fear. It could also explain why some students show a particular dislike of certain subjects that continue throughout their academic career. This could happen if a student is humiliated or punished in class by a teacher.

Principles of Classical Conditioning

Neutral stimulus.

In classical conditioning, a neutral stimulus (NS) is a stimulus that initially does not evoke a response until it is paired with the unconditioned stimulus.

For example, in Pavlov’s experiment, the bell was the neutral stimulus, and only produced a response when paired with food.

Unconditioned Stimulus

Unconditioned response.

In classical conditioning, an unconditioned response is an innate response that occurs automatically when the unconditioned stimulus is presented.

Pavlov showed the existence of the unconditioned response by presenting a dog with a bowl of food and measuring its salivary secretions.

Conditioned Stimulus

Conditioned response.

In classical conditioning, the conditioned response (CR) is the learned response to the previously neutral stimulus.

In Ivan Pavlov’s experiments in classical conditioning, the dog’s salivation was the conditioned response to the sound of a bell.

Acquisition

The process of pairing a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus to produce a conditioned response.

In the initial learning period, acquisition describes when an organism learns to connect a neutral stimulus and an unconditioned stimulus.

In psychology, extinction refers to the gradual weakening of a conditioned response by breaking the association between the conditioned and the unconditioned stimuli.

The weakening of a conditioned response occurs when the conditioned stimulus is repeatedly presented without the unconditioned stimulus.

For example, when the bell repeatedly rang, and no food was presented, Pavlov’s dog gradually stopped salivating at the sound of the bell.

Spontaneous Recovery

Spontaneous recovery is a phenomenon of Pavlovian conditioning that refers to the return of a conditioned response (in a weaker form) after a period of time following extinction.

It is the reappearance of an extinguished conditioned response after a rest period when the conditioned stimulus is presented alone.

For example, when Pavlov waited a few days after extinguishing the conditioned response, and then rang the bell once more, the dog salivated again.

Generalization

In psychology, generalization is the tendency to respond in the same way to stimuli similar (but not identical) to the original conditioned stimulus.

For example, in Pavlov’s experiment, if a dog is conditioned to salivate to the sound of a bell, it may later salivate to a higher-pitched bell.

Discrimination

In classical conditioning, discrimination is a process through which individuals learn to differentiate among similar stimuli and respond appropriately to each one.

For example, eventually, Pavlov’s dog learns the difference between the sound of the 2 bells and no longer salivates at the sound of the non-food bell.

Higher-Order Conditioning

Higher-order conditioning is when a conditioned stimulus is paired with a new neutral stimulus to create a second conditioned stimulus. For example, a bell (CS1) is paired with food (UCS) so that the bell elicits salivation (CR). Then, a light (NS) is paired with the bell.

Eventually, the light alone will elicit salivation, even without the presence of food. This demonstrates higher-order conditioning, where the conditioned stimulus (bell) serves as an unconditioned stimulus to condition a new stimulus (light).

Critical Evaluation

Practical applications.

The principles of classical conditioning have been widely and effectively applied in fields like behavioral therapy, education, and advertising. Therapies like systematic desensitization use classical conditioning to help eliminate phobias and anxiety.

The behaviorist approach has been used in the treatment of phobias, and systematic desensitization . The individual with the phobia is taught relaxation techniques and then makes a hierarchy of fear from the least frightening to the most frightening features of the phobic object.

He then is presented with the stimuli in that order and learns to associate (classical conditioning) the stimuli with a relaxation response. This is counter-conditioning.

Explaining involuntary behaviors

Classical conditioning helps explain some reflexive or involuntary behaviors like phobias, emotional reactions, and physiological responses. The model shows how these can be acquired through experience.

The process of classical conditioning can probably account for aspects of certain other mental disorders. For example, in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), sufferers tend to show classically conditioned responses to stimuli present at the time of the traumatizing event (Charney et al., 1993).

However, since not everyone exposed to the traumatic event develops PTSD, other factors must be involved, such as individual differences in people’s appraisal of events as stressors and the recovery environment, such as family and support groups.

Supported by substantial experimental evidence

There is a wealth of experimental support for basic phenomena like acquisition, extinction, generalization, and discrimination. Pavlov’s original experiments on dogs and subsequent studies have demonstrated classical conditioning in animals and humans.

There have been many laboratory demonstrations of human participants acquiring behavior through classical conditioning. It is relatively easy to classically condition and extinguish conditioned responses, such as the eye-blink and galvanic skin responses.

A strength of classical conditioning theory is that it is scientific . This is because it’s based on empirical evidence carried out by controlled experiments . For example, Pavlov (1902) showed how classical conditioning could be used to make a dog salivate to the sound of a bell.

Supporters of a reductionist approach say that it is scientific. Breaking complicated behaviors down into small parts means that they can be scientifically tested. However, some would argue that the reductionist view lacks validity . Thus, while reductionism is useful, it can lead to incomplete explanations.

Ignores biological predispositions

Organisms are biologically prepared to associate certain stimuli over others. However, classical conditioning does not sufficiently account for innate predispositions and biases.

Classical conditioning emphasizes the importance of learning from the environment, and supports nurture over nature.

However, it is limiting to describe behavior solely in terms of either nature or nurture , and attempts to do this underestimate the complexity of human behavior. It is more likely that behavior is due to an interaction between nature (biology) and nurture (environment).

Lacks explanatory power

Classical conditioning provides limited insight into the cognitive processes underlying the associations it describes.

However, applying classical conditioning to our understanding of higher mental functions, such as memory, thinking, reasoning, or problem-solving, has proved more problematic.

Even behavior therapy, one of the more successful applications of conditioning principles to human behavior, has given way to cognitive–behavior therapy (Mackintosh, 1995).

Questionable ecological validity

While lab studies support classical conditioning, some question how well it holds up in natural settings. There is debate about how automatic and inevitable classical conditioning is outside the lab.

In normal adults, the conditioning process can be overridden by instructions: simply telling participants that the unconditioned stimulus will not occur causes an instant loss of the conditioned response, which would otherwise extinguish only slowly (Davey, 1983).

Most participants in an experiment are aware of the experimenter’s contingencies (the relationship between stimuli and responses) and, in the absence of such awareness often fail to show evidence of conditioning (Brewer, 1974).

Evidence indicates that for humans to exhibit classical conditioning, they need to be consciously aware of the connection between the conditioned stimulus (CS) and the unconditioned stimulus (US). This contradicts traditional theories that humans have two separate learning systems – one conscious and one unconscious – that allow conditioning to occur without conscious awareness (Lovibond & Shanks, 2002).

There are also important differences between very young children or those with severe learning difficulties and older children and adults regarding their behavior in a variety of operant conditioning and discrimination learning experiments.

These seem largely attributable to language development (Dugdale & Lowe, 1990). This suggests that people have rather more efficient, language-based forms of learning at their disposal than just the laborious formation of associations between a conditioned stimulus and an unconditioned stimulus.

Ethical concerns

The principles of classical conditioning raise ethical concerns about manipulating behavior without consent. This is especially true in advertising and politics.

- Manipulation of preferences – Classical conditioning can create positive associations with certain brands, products, or political candidates. This can manipulate preferences outside of a person’s rational thought process.

- Encouraging impulsive behaviors – Conditioning techniques may encourage behaviors like impulsive shopping, unhealthy eating, or risky financial choices by forging positive associations with these behaviors.

- Preying on vulnerabilities – Advertisers or political campaigns may exploit conditioning techniques to target and influence vulnerable demographic groups like youth, seniors, or those with mental health conditions.

- Reduction of human agency – At an extreme, the use of classical conditioning techniques reduces human beings to automata reacting predictably to stimuli. This is ethically problematic.

Deterministic theory

A final criticism of classical conditioning theory is that it is deterministic . This means it does not allow the individual any degree of free will. Accordingly, a person has no control over the reactions they have learned from classical conditioning, such as a phobia.

The deterministic approach also has important implications for psychology as a science. Scientists are interested in discovering laws that can be used to predict events.

However, by creating general laws of behavior, deterministic psychology underestimates the uniqueness of human beings and their freedom to choose their destiny.

The Role of Nature in Classical Conditioning

Behaviorists argue all learning is driven by experience, not nature. Classical conditioning exemplifies environmental influence. However, our evolutionary history predisposes us to learn some associations more readily than others. So nature also plays a role.

For example, PTSD develops in part due to strong conditioning during traumatic events. The emotions experienced during trauma lead to neural activity in the amygdala , creating strong associative learning between conditioned and unconditioned stimuli (Milad et al., 2009).

Individuals with PTSD show enhanced fear conditioning, reflected in greater amygdala reactivity to conditioned threat cues compared to trauma-exposed controls. In addition to strong initial conditioning, PTSD patients exhibit slower extinction to conditioned fear stimuli.

During extinction recall tests, PTSD patients fail to show differential skin conductance responses to extinguished versus non-extinguished cues, indicating impaired retention of fear extinction. Deficient extinction retention corresponds to reduced activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus and heightened dorsal anterior cingulate cortex response during extinction recall in PTSD patients.

In influential research on food conditioning, John Garcia found that rats easily learned to associate a taste with nausea from drugs, even if illness occurred hours later.

However, conditioning nausea to a sight or sound was much harder. This showed that conditioning does not occur equally for any stimulus pairing. Rather, evolution prepares organisms to learn some associations that aid survival more easily, like linking smells to illness.

The evolutionary significance of taste and nutrition ensures robust and resilient classical conditioning of flavor preferences, making them difficult to reverse (Hall, 2002).

Forming strong and lasting associations between flavors and nutrition aids survival by promoting the consumption of calorie-rich foods. This makes flavor conditioning very robust.

Repeated flavor-nutrition pairings in these studies lead to overlearning of the association, making it more resistant to extinction.

The learning is overtrained, context-specific, and subject to recovery effects that maintain the conditioned behavior despite extinction training.

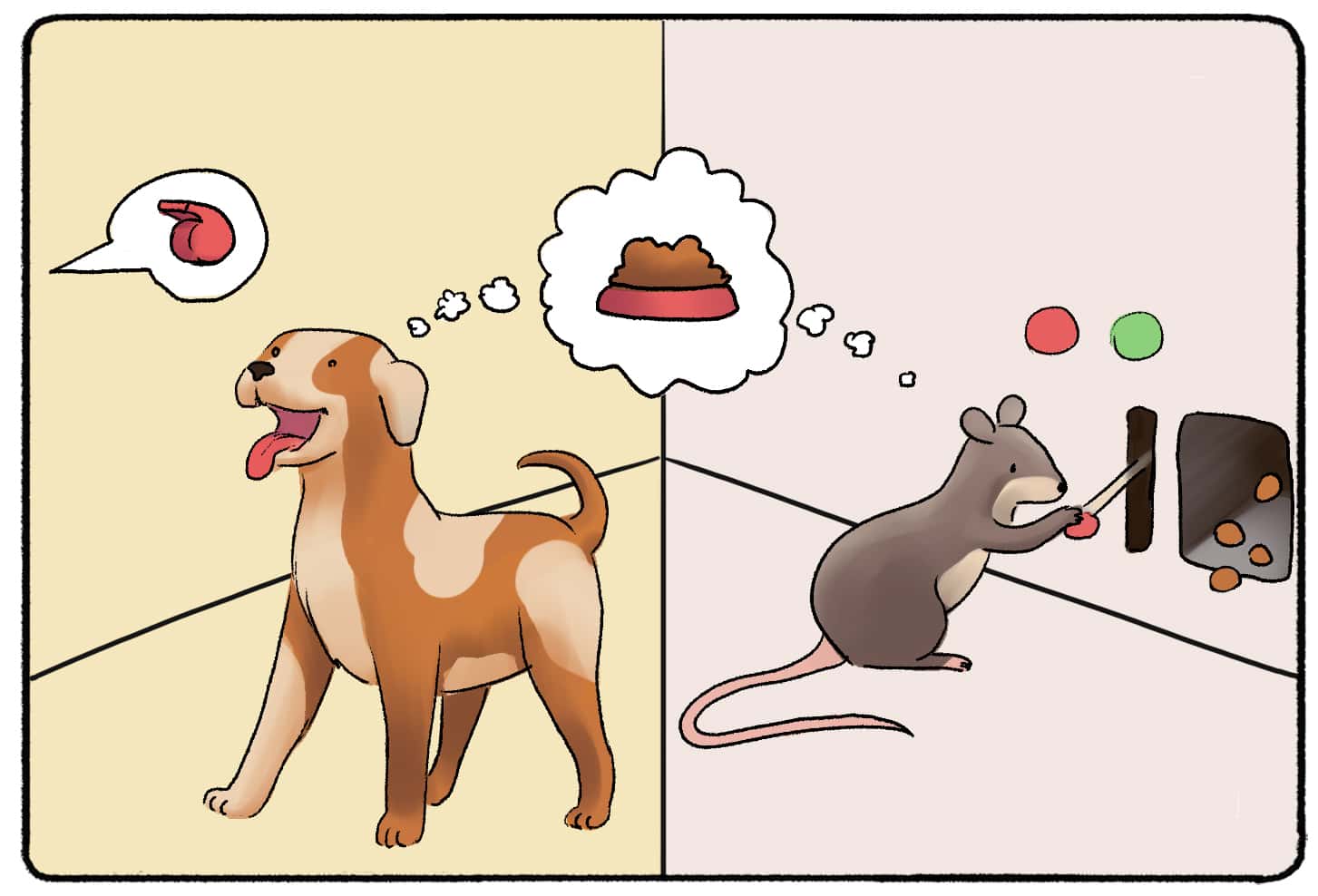

Classical vs. operant condioning

In summary, classical conditioning is about passive stimulus-response associations, while operant conditioning is about actively connecting behaviors to consequences. Classical works on reflexes and operant on voluntary actions.

- Stimuli vs consequences : Classical conditioning focuses on associating two stimuli together. For example, pairing a bell (neutral stimulus) with food (reflex-eliciting stimulus) creates a conditioned response of salivation to the bell. Operant conditioning is about connecting behaviors with the consequences that follow. If a behavior is reinforced, it will increase. If it’s punished, it will decrease.

- Passive vs. active : In classical conditioning, the organism is passive and automatically responds to the conditioned stimulus. Operant conditioning requires the organism to perform a behavior that then gets reinforced or punished actively. The organism operates on the environment.

- Involuntary vs. voluntary : Classical conditioning works with involuntary, reflexive responses like salivation, blinking, etc. Operant conditioning shapes voluntary behaviors that are controlled by the organism, like pressing a lever.

- Association vs. reinforcement : Classical conditioning relies on associating stimuli in order to create a conditioned response. Operant conditioning depends on using reinforcement and punishment to increase or decrease voluntary behaviors.

Learning Check

- In Ivan Pavlov’s famous experiment, he rang a bell before presenting food powder to dogs. Eventually, the dogs salivated at the mere sound of the bell. Identify the neutral stimulus, unconditioned stimulus, unconditioned response, conditioned stimulus, and conditioned response in Pavlov’s experiment.

- A student loves going out for pizza and beer with friends on Fridays after class. Whenever one friend texts the group about Friday plans, the student immediately feels happy and excited. The friend starts texting the group on Thursdays when she wants the student to feel happier. Explain how this is an example of classical conditioning. Identify the UCS, UCR, CS, and CR.

- A college student is traumatized after a car accident. She now feels fear every time she gets into a car. How could extinction be used to eliminate this acquired fear?

- A professor always slams their book on the lectern right before giving a pop quiz. Students now feel anxiety whenever they hear the book slam. Is this classical conditioning? If so, identify the NS, UCS, UCR, CS, and CR.

- Contrast classical conditioning and operant conditioning. How are they similar and different? Provide an original example of each type of conditioning.

- How could the principles of classical conditioning be applied to help students overcome test anxiety?

- Explain how taste aversion learning is an adaptive form of classical conditioning. Provide an original example.

- What is second-order conditioning? Give an example and identify the stimuli and responses.

- What is the role of extinction in classical conditioning? How could extinction be used in cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders?

Bouton, M. E., Mineka, S., & Barlow, D. H. (2001). A modern learning theory perspective on the etiology of panic disorder . Psychological Review , 108 (1), 4.

Bremner, J. D., Southwick, S. M., Johnson, D. R., Yehuda, R., & Charney, D. S. (1993). Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. The American journal of psychiatry .

Brewer, W. F. (1974). There is no convincing evidence for operant or classical conditioning in adult humans.

Carter, B. L., & Tiffany, S. T. (1999). Meta‐analysis of cue‐reactivity in addiction research. Addiction, 94 (3), 327-340.

Davey, B. (1983). Think aloud: Modeling the cognitive processes of reading comprehension. Journal of Reading, 27 (1), 44-47.

Dugdale, N., & Lowe, C. F. (1990). Naming and stimulus equivalence.

Garcia, J., Ervin, F. R., & Koelling, R. A. (1966). Learning with prolonged delay of reinforcement. Psychonomic Science, 5 (3), 121–122.

Garcia, J., Kimeldorf, D. J., & Koelling, R. A. (1955). Conditioned aversion to saccharin resulting from exposure to gamma radiation. Science, 122 , 157–158.

Hall, G. (2022). Extinction of conditioned flavor preferences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning and Cognition .

Logan, C. A. (2002). When scientific knowledge becomes scientific discovery: The disappearance of classical conditioning before Pavlov . Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences , 38 (4), 393-403.

Lovibond, P. F., & Shanks, D. R. (2002). The role of awareness in Pavlovian conditioning: empirical evidence and theoretical implications. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes , 28 (1), 3.

Milad, M. R., Pitman, R. K., Ellis, C. B., Gold, A. L., Shin, L. M., Lasko, N. B.,…Rauch, S. L. (2009). Neurobiological basis of failure to recall extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 66 (12), 1075–82.

Pavlov, I. P. (1897/1902). The work of the digestive glands . London: Griffin.

Thanellou, A., & Green, J. T. (2011). Spontaneous recovery but not reinstatement of the extinguished conditioned eyeblink response in the rat. Behavioral Neuroscience , 125 (4), 613.

Watson, J. B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist views it . Psychological Review, 20 , 158–177.

Watson, J.B. (1913). Psychology as the behaviorist Views It. Psychological Review, 20 , 158-177.

Watson, J. B. (1924). Behaviorism . New York: People’s Institute Publishing Company.

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions . Journal of experimental psychology, 3 (1), 1.

Learn More Psychology

- Behavioral Psychology

Pavlov's Dogs and Classical Conditioning

How pavlov's experiments with dogs demonstrated that our behavior can be changed using conditioning..

Permalink Print |

One of the most revealing studies in behavioral psychology was carried out by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936) in a series of experiments today referred to as 'Pavlov's Dogs'. His research would become renowned for demonstrating the way in classical conditioning (also referred to as Pavlovian conditioning ) could be used to cultivate a particular association between the occurrence of one event in the anticipation of another.

- Conditioning

- Stimulus-Response Theory

- Reductionism in Psychology

- What Factors Affect Classical Conditioning?

- Imprinting and Relationships

Pavlov's Dog Experiments

Pavlov came across classical conditioning unintentionally during his research into animals' gastric systems. Whilst measuring the salivation rates of dogs, he found that they would produce saliva when they heard or smelt food in anticipation of feeding. This is a normal reflex response which we would expect to happen as saliva plays a role in the digestion of food.

Did You Know?

Psychologist Edwin Twitmyer at the University of Pennsylvania in the U.S. discovered classical conditioning at approximately the same time as Pavlov was conducting his research ( Coon, 1982 ). 1 However, the two were unaware of each other's research in this case of simultaneous discovery , and Pavlov received credit for the findings.

However, the dogs also began to salivate when events occurred which would otherwise be unrelated to feeding. By playing sounds to the dogs prior to feeding them, Pavlov showed that they could be conditioned to unconsciously associate neutral, unrelated events with being fed 2 .

Experiment Procedure

Pavlov's dogs were each placed in an isolated environment and restrained in a harness, with a food bowl in front of them and a device was used to measure the rate at which their saliva glands made secretions. These measurements would then be recorded onto a revolving drum so that Pavlov could monitor salivation rates throughout the experiments.

He found that the dogs would begin to salivate when a door was opened for the researcher to feed them.

This response demonstrated the basic principle of classical conditioning . A neutral event, such as opening a door (a neutral stimulus , NS) could be associated with another event that followed - in this case, being fed (known as the unconditioned stimulus , UCS). This association could be created through repeating the neutral stimulus along with the unconditioned stimulus, which would become a conditioned stimulus , leading to a conditioned response : salivation.

Pavlov continued his research and tested a variety of other neutral stimuli which would otherwise be unlinked to the receipt of food. These included precise tones produced by a buzzer, the ticking of a metronome and electric shocks .

The dogs would demonstrate a similar association between these events and the food that followed.

NEUTRAL STIMULUS (NS, eg. tone) > UNCONDITIONED STIMULUS (UCS, eg. receiving food)

when repeated leads to:

CONDITIONED STIMULUS (CS, eg. tone) > CONDITIONED RESPONSE (CR, eg. salivation)

The implications for Pavlov's findings are significant as they can be applied to many animals, including humans.

For example, when you first saw someone holding a balloon and a pin close to it, you may have watched in anticipation as they burst the balloon. After this had happened multiple times, you would associate holding the pin to the balloon with the 'bang' that followed. Like Pavlov's dogs, classical conditioning was leading you to associate a neutral stimulus (the pin approaching a balloon) with bursting of the balloon, leading to a conditioned response (flinching, wincing or plugging one's ears) to this now conditioned stimulus.

- Craik & Lockhart (1972) Levels of Processing Theory

Let us look now at some of the nuances of Pavlov's findings in relation to classical conditioning.

'Unconditioning' through experimental extinction

Once an animal has been inadvertently conditioned to produce a response to a stimulus, can this association ever be broken?

Pavlov presented the dogs with a tone which they would come to associate with food. He then played the tone but did not follow that by rewarding the dogs with food.

After he made the sound without food numerous times, the dogs' produced less saliva as the conditioning underwent experimental extinction - a case of 'unlearning' the association.

When experimental extinction occurs, is the association permanently broken?

Pavlov's research would suggest that it remains but is inactive after extinction, and can be re-activated by reinstating, for example, the food reward, as it was given during the original conditioning. This phenomenon is known as spontaneous recovery .

Forward Conditioning vs Backward Conditioning

During conditioning, it is important that the neutral stimulus (NS) is presented before the unconditioned stimulus (UCS) in order for learning to take place. This forward conditioning is more likely to lead to a conditioned response than when the neutral stimulus is presented after the conditioned stimulus has been provided ( backward conditioning ).

In the case of Pavlov's dogs, the tone must be played to the subject prior to the food being provided. Making a sound after the dogs have been fed may not lead to a conditioned association being made between the events.

Carr and Freeman (1919) attempted both forward and backward conditioning in rats, between a buzzer sound and closed doors in a maze. They found backward conditioning to be ineffective when compared to forward conditioning. 4

Delay Conditioning vs Trace Conditioning

We may use forward conditioning in one of two forms:

Delay Conditioning - when the unconditioned stimulus is provided prior to and during the unconditioned stimulus - there is a period of overlap where the neutral and unconditioned stimulus are given simultaneously, e.g. a buzzer sound begins, and after 10 seconds, food is given whilst the buzzer continues.

Trace Conditioning - when there is a delay after the unconditioned stimulus has been provided before the unconditioned stimulus is presented to the subject, e.g. buzzer sounds for 10 seconds, stops and after 10 seconds of silence (the trace interval ), food is presented.

Discussing delay conditioning, Pavlov (1927) asserted that the longer the delay between the stimuli, the more delayed the response would be 5 .

Temporal Conditioning

So far, we have looked at conditioning in which a neutral stimulus is key to eliciting a desired response. However, if an unconditioned stimulus is provided at regular intervals, even without a preceding neutral stimulus, animals' sense of timing will enable conditioning to take place, and a response may occur in time with the intervals.

For example, in a study in which rats were fed at either random or regular intervals, Kirkpatrick and Church (2003) found that the subjects underwent temporal conditioning in the anticipation of food when they were fed at set intervals. 6

Generalisation

Pavlov noticed that once neutral stimulus had been associated with an unconditioned stimulus, the conditioned stimulus could vary and the dogs would still generate a similar response. For example, once specific tone of buzzer sound was associated with food, differing toned buzzer sounds would solicit a conditioned response.

Nonetheless, the closer the stimulus was to the original stimulus used in conditioning, the clearer the response would be. This correlation between stimulus accuracy and response is referred to as a generalisation gradient , and has been demonstrated in studies such as Meulders et al (2013) . 7

Modern Classical Conditioning

Pavlov's dog experiments are still discussed today and have influenced many later ideas in psychology. The U.S. psychologist John B. Watson was impressed by Pavlov's findings and reproduced classical conditioning in the Little Albert Experiment (Watson, 1920), in which a subject was unethically conditioned to associate furry stimuli such as rabbits with a loud noise, and subsequently developed a fear of rats. 8

- Behavioral Approach

The numerous studies following the experiments, which have demonstrated classical conditioning using a variety of methods, also show the replicability of Pavlov's research, helping it to be recognised as an important unconscious influence of human behavior. This has helped the theory to be recognised and applied in many real life situations, from training dogs to creating associations in today's product advertisements.

Continue Reading

- Coon, D.J. (1982). Eponymy, obscurity, Twitmyer, and Pavlov. Journal of the History of Behavioral Science . 18 (3). 255-62.

- Pavlov, I.P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Pavlov/ .

- Craik, F.I.M. and Lockhart, R.S. (1972). Levels of Processing: A Framework for Memory Research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Visual Behavior . 11 (6). 671-684.

- Carr, H. and Freeman A. (1919). Time relationships in the formation of associations. Psychology Review . 26 (6). 335-353.

- Pavlov, I.P. (1927). Conditioned Reflexes: An investigation of the physiological activity of the cerebral cortex. Retrieved from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Pavlov/lecture6.htm .

- Kirkpatrick, K and Church, R.M. (2003). Tracking of the expected time to reinforcement in temporal conditioning processes. Learning & Behavior . 31 (1). 3-21.

- Meulders A, Vandebroek, N. Vervliet, B. and Vlaeyen, J.W.S. (2013). Generalization Gradients in Cued and Contextual Pain-Related Fear: An Experimental Study in Health Participants. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience , 7 (345). 1-12.

- Watson, J.B. and Rayner, R. (1920). Conditioned Emotional Reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology . 3 (1). 1-14.

- Watson, J.B. (1913). Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It. Psychological Review . (Watson, 1913). 20 . 158-177.

Which Archetype Are You?

Are You Angry?

Windows to the Soul

Are You Stressed?

Attachment & Relationships

Memory Like A Goldfish?

31 Defense Mechanisms

Slave To Your Role?

Are You Fixated?

Interpret Your Dreams

How to Read Body Language

How to Beat Stress and Succeed in Exams

More on Behavioral Psychology

Dressing To Impress

The psychology driving our clothing choices and how fashion affects your dating...

Fashion Psychology: What Clothes Say About You

Shock Therapy

Aversion therapy uses the principle that new behavior can be 'learnt' in order...

Immerse To Overcome?

If you jumped out of a plane, would you overcome your fear of heights?

Imprinting: Why First Impressions Matter

How first impressions from birth influence our relationship choices later in...

Bats & Goodwill

Why do we help other people? When Darwin introduced his theory of natural...

Sign Up for Unlimited Access

- Psychology approaches, theories and studies explained

- Body Language Reading Guide

- How to Interpret Your Dreams Guide

- Self Hypnosis Downloads

- Plus More Member Benefits

You May Also Like...

Nap for performance, dark sense of humor linked to intelligence, why do we dream, persuasion with ingratiation, making conversation, brainwashed, psychology of color, master body language, psychology guides.

Learn Body Language Reading

How To Interpret Your Dreams

Overcome Your Fears and Phobias

Psychology topics, learn psychology.

- Access 2,200+ insightful pages of psychology explanations & theories

- Insights into the way we think and behave

- Body Language & Dream Interpretation guides

- Self hypnosis MP3 downloads and more

- Eye Reading

- Stress Test

- Cognitive Approach

- Fight-or-Flight Response

- Neuroticism Test

© 2024 Psychologist World. Home About Contact Us Terms of Use Privacy & Cookies Hypnosis Scripts Sign Up

Ivan Pavlov (Biography + Experiments)

When most people think of Ivan Pavlov two thoughts readily come to mind. The first is Pavlov was an amazing psychologist. The second is he worked with dogs. But although Pavlov did some incredible work with dogs and made major contributions to the field of psychology, the truth is he was not a psychologist at all. So, who exactly was he?

Who Is Ivan Pavlov?

Ivan Petrovich Pavlov was a Russian physiologist who is best known for discovering the concept of classical conditioning. He was born on September 14, 1849, in Ryazan, Russia. Pavlov won the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1904. He died in Leningrad on February 27, 1936.

His Early Years

Ivan Pavlov was the eldest child of Varvara Ivanovna Uspenskaya and Peter Dmitrievich Pavlov. He had ten siblings. Pavlov’s mother was a homemaker and his father was a Russian Orthodox priest at the village church. His grandfather also worked at the church as a sexton.

Pavlov was a good reader by the time he was seven years old. However, he was seriously hurt when he fell from a high wall during his childhood. His injuries caused him to spend most of his early years at home and in his family garden. During this part of his life, Pavlov grew to love nature, gardening, and working with his hands.

As the years passed, Pavlov’s body slowly began to heal. He was eleven years old when he started classes at the Ryazan church school.

What did Ivan Pavlov Study?

After Pavlov completed his classes at the local church school, he enrolled at the seminary in Ryazan. He was immediately impressed by his teachers’ desire to share religious knowledge with him. But despite growing up in a religious household, Pavlov struggled to accept religion. He soon began to wonder if studying theology was right for him.

While at the seminary Pavlov became inspired by the ideas of Dmitry Pisarev—a radical Russian writer and social critic, and Ivan M. Sechenov—a prominent Russian physiologist. Their progressive ideas convinced Pavlov to drop his religious studies at the seminary and devote his life to science. Unsurprisingly, Pavlov's father was furious when he found out. However, Pavlov was determined to live his life the way he wanted.

University of St. Petersburg

In 1870, Pavlov was accepted at the University of St. Petersburg. He enrolled in the physics and mathematics department because he wanted to study natural science. Pavlov spent much of his time studying chemistry and physiology. His first-year chemistry professor was Dmitri Mendeleev, the man who invented the periodic table of elements.

During his first research course in natural science, Pavlov and another student named Afanasyev published a research paper on the physiology of pancreatic nerves. They received much praise and were awarded a gold medal for their work. Overall, Pavlov's grades at the University of St. Petersburg were excellent. He completed his degree in natural science in 1875.

Pavlov's passion for physiology motivated him to continue his studies at the Imperial Academy of Medical Surgery. While there, he worked as an assistant to his former teacher Elias von Cyon—a Russian-French physiologist. However, von Cyon was forced to relocate to Paris when students protested his political views. When von Cyon was replaced by another instructor, Pavlov quit the department.

Pavlov spent two years as an assistant at the physiological department of the Veterinary Institute. During that time he worked on his medical dissertation on the circulatory system. In 1878, Pavlov was offered the position of director of the Physiological Laboratory at Sergey Botkin’s clinic. Botkin was a famous clinician and therapist at the time and was later regarded as one of the pillars of modern medical science in Russia.

Pavlov graduated from the Academy in 1879. At his graduation, he was awarded another gold medal for his outstanding research. He also won a fellowship at the Academy. This fellowship and his role at the Botkin Clinic allowed him to continue his research until he completed his dissertation on The Centrifugal Nerves of the Heart in 1883.

Work with Carl Ludwig

In 1884, Pavlov went abroad to continue his studies. First, he worked under the supervision of Carl Ludwig—a well known cardiovascular physiologist—in Leipzig, Germany. He then went to Breslau, Poland to assist renowned physiologist Rudolf Heidenhain in his study of digestion in dogs. After his studies were complete, Pavlov returned to Russia in 1886.

Pavlov accepted the role of professor of Pharmacology at the Military Medical Academy (formerly called the Imperial Academy of Medical Surgery) in 1890. Less than one year later, he was also invited to serve as the head of the Physiology Department at the Institute of Experimental Medicine. Pavlov was appointed to the Chair of Physiology at the Military Medical Academy in 1895—a role he occupied for 30 years. However, most of his research on the physiology of digestion was conducted at the Institute of Experimental Medicine, where he worked for 45 years.

Pavlov's Dog Experiment

The bulk of Pavlov’s research was conducted from 1891 to the early 1900s. In 1902 he was researching how dogs salivated in response to being fed. To measure the amount of saliva produced, he surgically implanted a small tube into the cheek of each dog. His prediction was that salivation would begin only after the food was placed in front of the dogs.

However, Pavlov soon noticed something quite interesting. At first, the dogs salivated only if they were presented with food. But later in the experiment, the dogs began salivating when they heard Pavlov’s assistant coming with their food. Were the dogs producing more saliva because they could smell the food as it was brought closer? Apparently not, because the dogs still salivated even when Pavlov’s assistant came empty-handed.

Pavlov was fascinated by these results. It did not take him long to figure out that other objects or events would trigger the same salivation response if the dogs associated those objects or events with food. Pavlov immediately realized he had made an important scientific discovery. He spent the rest of his professional life studying this type of learning.

Discovering Pavlovian Conditioning

Pavlovian conditioning (also called classical conditioning ) refers to the process of learning through association. It was first documented by Ivan Pavlov in 1902 when he was researching digestion in dogs. Although he was a brilliant man, Pavlov made this discovery quite by accident. Nevertheless, classical conditioning went on to have a major influence in the field of psychology.

Pavlovian conditioning assumes there are some behaviors that humans and animals do not need to learn. Instead, the response or reflex occurs naturally whenever it is triggered. In Pavlov’s case, the dogs salivated (unconditioned reflex) when they were presented with food (unconditioned stimulus). In this case, the stimulus and reflex are described as “unconditioned” because the reaction is hard-wired into the dogs and required no learning.

However, Pavlov knew that the dogs did learn new things as the experiment went on. He came to this conclusion because initially, the dogs only salivated when they were given food. At the start of the experiment they did not salivate when they heard the footsteps of his assistant. The fact that the dogs later started to salivate when they heard the footsteps shows they had learned to associate Pavlov’s assistant with the food they desired.

Stimuli in Classical Conditioning

Pavlov's lab assistant can be thought of as a “neutral stimulus” at the beginning of the experiment. This is because his presence caused no response from the dogs. As the experiment went on, the dogs linked the lab assistant (neutral stimulus) with food (unconditioned stimulus). After the association was formed, the dogs began salivating whenever they heard the assistant’s footsteps.

If the dogs could learn to associate his assistant with food, Pavlov believed they could learn to associate other things with food. To test if his belief was correct, he decided to use a metronome as his neutral stimulus. A metronome is a device that produces a click or tone at regular intervals.

Under normal circumstances, dogs do not salivate when they hear a tone. But if the tone was successfully linked with food, Pavlov believed the dogs would salivate each time they heard it.

How Did Pavlov's Dog Experiments Work?

So Pavlov started to play the tone before he fed his dogs. He repeated the process for days. After some time had passed, he played the tone without presenting any food to the dogs. As he expected, his dogs showed an increase in salivation whenever they heard the tone.

Although the dogs had no response to the tone at the start of the experiment, they had learned a new response by the end of it. And as this response needed to be learned, Pavlov called it a “conditional reflex.” Pavlov also recognized that the tone was no longer a neutral stimulus. By linking it with food (unconditioned stimulus), the tone had become a “conditioned stimulus.”

There are many reports that Pavlov used a bell for the experiments he conducted with his dogs. And he may have used one on occasion. However, Pavlov wanted to control the intensity, quality, and duration of the stimuli. So he relied heavily on a metronome, harmonium, buzzer, and even electric shocks for most of his experiments.

There was one more thing Pavlov discovered during his experiment. He realized that the tone (initially a neutral stimulus) and the food (unconditioned stimulus) needed to be presented close together in time for the link to be made. He referred to this requirement as the law of temporal contiguity. If there is too much time between the playing of the tone and the presentation of the food, the dogs would not learn to salivate when they heard the tone.

Behaviorism Theory

Behaviorism is a theory that suggests human and animal psychology can be understood by studying observable actions. While many forms of psychology emphasize thoughts and feelings, behaviorists believe the “inner world” is not important because it cannot be seen or accurately measured. Behaviorists believe all human behavior is learned by interacting with the environment. Consequently, any person can be trained to become an expert in any task, regardless of his or her personality, culture, or genetic traits.

John B. Watson

Behaviorism was developed by American psychologist John B. Watson in 1913. He was greatly influenced by the work and observations of Ivan Pavlov. Watson believed all facets of human psychology could be explained by Pavlovian conditioning. He denied the existence of the mind, believed all humans begin as a blank slate, and claimed speech, emotional reactions, and other complex behaviors were nothing more than learned responses to environmental stimuli.

B.F. Skinner

Another prominent behaviorist who was heavily influenced by Pavlov is Burrhus Frederic Skinner . While Watson expanded on methodological behaviorism, Skinner pioneered a different approach called radical behaviorism. Skinner is widely considered to be the father of operant conditioning—a learning process that is different from classical conditioning. Skinner actually had plans to major in English and become a novelist before he was introduced to Pavlov’s work in 1927.

Although many people think Pavlov did not care about studying things that could not be measured, he never made those claims himself. In fact, he viewed the human mind as a great mystery. If scientists want to understand the human mind, the process has to begin somewhere. Pavlov believed the best approach was to begin with observation and hard data.

Pavlov's Impact on Psychology and Education

Classical conditioning has had a big impact on modern-day learning strategies. Although Pavlov worked with animals, he always believed the principles of classical conditioning can be applied to humans. A number of Pavlov’s basic ideas have been implemented in classrooms and other learning environments. Just as Pavlov used different stimuli to increase or decrease specific behaviors in his dogs, many teachers change their tools, instructions, or environment to influence the behavior of their students and increase learning.

If a teacher is faced with an ongoing problem behavior from a student, the teacher may try to eliminate or change the behavior. One way to do this is by changing something in the learning environment that triggers that specific behavior. So the teacher may move the student to a different seat, change the lights in the classroom, or close an open window if they trigger the bad behavior. The teacher may also try to change her content or modify the way it is presented in order to boost learning.

These strategies are particularly effective for teaching people with behavior problems or learning disabilities. They have been implemented in many schools, homes, and health centers around the world.

Ivan Pavlov's Accomplishments and Awards

Pavlov published many research papers and lectures throughout his long professional career. Some of his more notable works have been compiled into a few books such as The Work of the Digestive Glands (1897), Conditioned Reflexes (1926), and Psychopathology and Psychiatry (1961). His biography, Pavlov: A Biography was written by Boris Babkin and published in 1949. A more recent biography, Ivan Pavlov: A Russian Life in Science, was written by Daniel P. Todes and published in 2014.

Nobel Prize

Pavlov was nominated for the Nobel Prize from 1901 to 1904. However, he did not win the prize for the first three years because his nominations were tied to a variety of findings rather than a specific discovery. When he was first nominated in 1901, he was already well known among physiologists, especially those who studied digestion. However, Pavlov's research on conditioned reflexes was not published until 1902 and it may have taken a while for this work to penetrate the field of psychology.

In 1904, Pavlov was finally awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. He received the award for his outstanding research on digestion in animals. This research involved removing a dog's esophagus and creating a fistula or tunnel in a dog’s throat so that if the dog ate, the food would not enter its stomach. Pavlov would then collect and test the different secretions along the dog’s digestive system.

Although Pavlov’s methods may seem extreme by today's standards, he always did his best to keep his dogs fed and healthy. He viewed them as very valuable for his work. When his dogs eventually died, he found effective ways to get more. He would take in strays or even pay thieves to steal dogs from other people.

After Pavlov won the Nobel Prize, he drew the attention of many other scientists from around the world. American psychologists, in particular, became more aware of his work and were more willing to test his findings on conditional reflex.

Personal Life and Death

Throughout his life, Pavlov was never easy to get along with. In his childhood days, he often felt uncomfortable around his parents. He was also known to be a volatile and difficult student. When he opened his lab as an adult, his staff knew to avoid him if he was having one of his many bad days.

Ivan Pavlov Children and Wife

Ivan Pavlov met Seraphima Vasilievna Karchevskaya (also known as Sara) in 1878 or 1879. At the time, Sara was a student at the Pedagogical Institute. It did not take long for the young couple to fall in love. They were married on May 1, 1881.

When Sara became pregnant for the first time, she had a miscarriage. The couple was very careful the second time Sara conceived, and she gave birth to a healthy baby boy named Mirchik. However, Mirchik died suddenly in childhood and this made Sara very depressed. Eventually, the couple had four more children. Their names were Vladimir, Victor, Vsevolod, and Vera.

Ivan and Sara Pavlov spent their first nine years as husband and wife in poverty. Due to their financial troubles, they were often forced to live in different homes so they could benefit from the hospitality of other people. Pavlov even grew potatoes and other crops outside his lab to help make ends meet. Once their finances became stable, Ivan and Sara were able to live together in the same house.

Pavlov was eventually able to earn money from health products he made in his lab. He sold the gastric juice he collected from his dogs as an effective treatment for indigestion. Of course, winning the Nobel Prize in 1904 brought monetary rewards. However, the ever-changing political scene in Russia made life difficult for him, his family, and his fellow scientists.

Cause of Death

On February 27, 1936, Ivan Pavlov passed away in Leningrad, Russia. He was 86 years old. He died from lung issues caused by pneumonia. Ever the researcher, Pavlov asked one of his students to sit beside his bed as he died so that the experience could be properly documented.

Related posts:

- The Little Albert Experiment

- Classical Conditioning (Memory Guide + Examples)

- Philip Zimbardo (Biography + Experiments)

- Albert Bandura (Biography + Experiments)

- Stimulus Response Theory (Thorndike's Research + Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Famous Psychologists:

Abraham Maslow

Albert Bandura

Albert Ellis

Alfred Adler

Beth Thomas

Carl Rogers

Carol Dweck

Daniel Kahneman

David Dunning

David Mcclelland

Edward Thorndike

Elizabeth Loftus

Erik Erikson

G. Stanley Hall

George Kelly

Gordon Allport

Howard Gardner

Hugo Munsterberg

Ivan Pavlov

Jerome Bruner

John B Watson

John Bowlby

Konrad Lorenz

Lawrence Kohlberg

Leon Festinger

Lev Vygotsky

Martin Seligman

Mary Ainsworth

Philip Zimbardo

Rensis Likert

Robert Cialdini

Robert Hare

Sigmund Freud

Solomon Asch

Stanley Milgram

Ulric Neisser

Urie Bronfenbrenner

Wilhelm Wundt

William Glasser

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Pavlov’s Dog: The Psychology Experiment That Changed Everything

Pavlov’s Dog is a well-known experiment in psychology that has been taught for decades. Ivan Pavlov , a Russian physiologist, discovered classical conditioning through his experiments with dogs. He found that dogs could be trained to associate a sound with food, causing them to salivate at the sound alone.

The experiment began with Pavlov ringing a bell every time he fed his dogs. After a while, the dogs began to associate the sound of the bell with food and would salivate at the sound alone, even if no food was present. This became known as a conditioned response, where a previously neutral stimulus (the bell) became associated with a natural response (salivating).

The experiment has been used to explain many psychological phenomena, including addiction, phobias, and anxiety. It has also been applied in therapy, where patients can learn to associate positive experiences with previously negative stimuli. The Pavlov’s Dog experiment is a crucial part of psychology’s history and continues to be studied today.

Pavlov’s Life and Career

Ivan Pavlov was a Russian physiologist who lived from 1849 to 1936. He is best known for his work in classical conditioning, a type of learning that occurs when a neutral stimulus is consistently paired with a stimulus that elicits a response. Pavlov was born in Ryazan, Russia, and studied at the University of St. Petersburg, where he received his doctorate in 1879.

Pavlov’s early research focused on the digestive system, and he discovered that the secretion of gastric juice was not a passive process but rather a response to stimuli. This led him to develop the concept of the conditioned reflex, which he explored in detail in his famous experiments with dogs.

In these experiments, Pavlov trained dogs to associate the sound of a bell with food presentation. Over time, the dogs began to salivate at the sound of the bell, even when no food was present. This demonstrated that a neutral stimulus (the bell) could become associated with a natural response (salivation) through repeated pairings with a stimulus that elicits that response (food).

Pavlov’s work had a profound impact on the field of psychology, and his ideas continue to influence research today. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1904 for his work on the physiology of digestion. Still, his legacy is best remembered for his contributions to the study of learning and behavior.

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning is a type of learning that occurs when a neutral stimulus is repeatedly paired with a stimulus that naturally elicits a response. Over time, the neutral stimulus becomes associated with the natural stimulus and begins to produce the same response. Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov first studied this type of learning in the late 1800s.

One of the most famous examples of classical conditioning is Pavlov’s experiment with dogs. In this experiment, Pavlov rang a bell every time he fed the dogs. Eventually, the dogs began to salivate at the sound of the bell, even when no food was present. The sound of the bell had become associated with the food, and the dogs had learned to associate the two stimuli.

Classical conditioning can be used to explain a variety of behaviors and responses. For example, a person who has been in a car accident may develop a fear of driving. The sound of screeching tires or the sight of a car may become associated with the traumatic experience, causing the person to feel anxious or fearful when driving.

Classical conditioning can also be used to treat certain types of phobias and anxiety disorders. By gradually exposing a person to the feared stimulus in a safe and controlled environment, the person can learn to associate the stimulus with safety and relaxation rather than fear and anxiety.

Classical conditioning is a powerful tool for understanding how we learn and respond to environmental stimuli. By understanding the principles of classical conditioning, we can better understand our behaviors and emotions, as well as those of others around us.

Pavlov’s Experiments

Pavlov’s experiments with dogs revolutionized the field of psychology and laid the foundation for the study of classical conditioning. In this section, we will explore two aspects of his experiments: salivating dogs and conditioned responses.

Salivating Dogs

Pavlov observed that dogs would salivate when presented with food. However, he also noticed that the dogs would start salivating before the food was presented. This led him to hypothesize that the dogs were responding not just to the food but to other associated stimuli, such as the sound of the food being prepared or the sight of the person who fed them.

To test his hypothesis, Pavlov began a series of experiments where he would ring a bell before presenting the dogs with food. After a few repetitions, the dogs began to salivate at the sound of the bell alone, even when no food was present. This demonstrated that the dogs had learned to associate the sound of the bell with the presence of food and were responding accordingly.

Conditioned Response

Pavlov’s experiments with dogs led to the discovery of the conditioned response, the learned response to a previously neutral stimulus. In the case of Pavlov’s dogs, the sound of the bell was originally a neutral stimulus. Still, it became associated with food and, therefore, elicited a response (salivation) from the dogs.

The conditioned response is an essential concept in psychology, as it helps to explain how we learn to respond to various stimuli in our environment. For example, if we have a positive experience with a particular food, we may develop a conditioned response to the sight or smell of that food, even if we are not hungry.

Pavlov’s experiments with dogs were groundbreaking in psychology and led to the discovery of classical conditioning and the conditioned response. By demonstrating that animals (and humans) can learn to respond to previously neutral stimuli, Pavlov paved the way for further research into the mechanisms of learning and behavior.

Significance in Psychology

Pavlov’s dog experiment has been a significant discovery in psychology. It has paved the way for developing various theories and has been instrumental in understanding human behavior. In this section, we will discuss the significance of Pavlov’s dog experiment in the context of behaviorism and learning theories.

Behaviorism

Pavlov’s dog experiment has been a cornerstone in the development of behaviorism. Behaviorism is a school of thought in psychology that emphasizes the importance of observable behavior rather than internal mental states. Pavlov’s experiment demonstrated how a stimulus-response connection could be formed through conditioning. This concept has been used to explain various behaviors, such as phobias and addictions.

Learning Theories

Pavlov’s dog experiment has also been significant in developing learning theories . Learning theories are concerned with how people acquire new knowledge and skills. Pavlov’s experiment demonstrated how classical conditioning could teach animals new behaviors. This concept has been used to explain various learning phenomena, such as the acquisition of language and the development of social skills.

In conclusion, Pavlov’s dog experiment has been a significant discovery in psychology. It has been instrumental in the development of behaviorism and learning theories. By understanding the principles of classical conditioning, we can better understand human behavior and how we learn new skills and behaviors.

Implications in Modern Psychology

Pavlov’s dog experiments have had a significant impact on modern psychology. His theory of classical conditioning has become a cornerstone of behaviorism, a school of thought that dominated psychology in the early 20th century. Today, it continues to influence psychologists and researchers in various fields.

One of the most significant implications of Pavlov’s work is the understanding of how learning takes place. His experiments showed that animals, including humans, can learn through association. This concept has been applied in many areas of modern psychology, including education, advertising, and even politics.

For example, in education, classical conditioning can improve students’ learning by associating positive experiences with specific subjects or activities. In advertising, classical conditioning can create positive associations between a product and a particular emotion or experience, influencing consumers’ purchasing decisions.